love, in Portugal:

these perfect pastries, melted;

now just down the block

love, in Portugal:

these perfect pastries, melted;

now just down the block

Just before the rain, we finished planting all the seeds. Pumpkin and yellow squash, red peppers and zucchini, cucumbers and cilantro.

I am so grateful for this downpour because it’s been a dry month, in more ways than one, for me. A year ago, when Muslim students spilled into my room at lunch to be far away from food during Ramadan, I decided to fast with them. I never told them that I rose before dawn to scarf down overnight oatmeal, avocados, and watermelon, that I drank two giant glasses of water to sustain myself for a busy day at school. I never told them, and they never asked, why I wasn’t eating either. But they would sit in my room and talk about the special meals their mothers would be preparing for that night’s Iftar. They would chat with each other, asking about when the next prayer time would be or what math homework they needed to do before that evening’s visit to the mosque.

There was a safety in that space, my classroom at lunch, the lights off, the sun streaming in through the cracks of the shades. There was no space for judgment or smells of others’ meals, and we were like friends, my students and me.

I cannot replicate it now, and I will never be a religious person, and quarantine is hard enough, but I decided to fast for the thirty days of Ramadan this year anyway. Why would I put myself through such torture when no one in my house would, when we’re already giving up so much right now, when I’m surrounded by a kitchen and pantry packed with food?

And what would anyone think, really, this stupid white girl appropriating another’s culture?

I didn’t talk about it with anyone outside of my family, really. A couple of friends. I wasn’t sure if I should say anything at all, out of respect, but I saw this article in the Washington Post and I felt better, six days into my decision.

Being at home has its benefits. I burn so many more calories at school, walking from desk to desk, from my classroom to the printer to the copier, to the bathroom, to the office for meetings, to chat with colleagues in other rooms. At home, I can sit on my couch with my puppy and listen to an audiobook and cross-stitch for hours. A few times I even took a nap, though I’m terrible at taking naps.

I barely slept for the past thirty days. Too much goes on in my house that is difficult for me to control right now. Everyone is in one mode or another of depression and anxiety because of this virus that is a weight on all of our lives, because of not wanting to or feeling comfortable about being at home with each other (rather than friends), because I was so stressed about my husband losing his job, and even once he miraculously got a new job in the midst of a pandemic, there was a lingering sense of remorse for all the worry I had wasted for three months.

So rising at 4:30 with my alarm barely happened. Most of the time my eyes popped open around 4:00, just when the birds started their pre-dawn chatter. My puppy thought I was so crazy that he didn’t even beg for bits of food or lick my plate, but rather sullenly remained sleeping on the couch until I roused him for our singular long walk, the only time I would have enough energy to walk 2-3 miles.

Because one thing I have learned about not eating or drinking even a sip of water for 14-15 hours is that it is the most exhausting thing I can imagine experiencing. By 6:00pm, I’d be shaky and loopy, trying to fix dinner with one of the kids. By 7:00, I’d be shaky and loopy with anticipation, so excited for the sweet taste of juice that I rarely drink but have enjoyed for the past month, for whatever concoction we were throwing together for that night’s meal, whether it simply be hot dogs and broccoli or fried chicken and fries.

It’s incredible how amazingly cool and refreshing that first sip of ice-cold juice is, that first bite of food that you want to hold in your mouth and allow your whole body to feel its nourishment. And after a few drinks and a few sips, despite being so starving, I’d feel full, yet still so exhausted that it wouldn’t be long before I’d crawl into bed, ready to begin again tomorrow.

It’s funny how the body works. How the mind works. How hard it was, day after day, wishing it would be over, wishing the new moon would come in its crescent beauty, wondering why I would choose to do this.

I saw so many perfect sunrises.

I spoke to my children with tears in my eyes and a shaky voice many times. There was a weakness there, an inability to scream or argue, that didn’t exist before.

I thought about my Muslim students, so isolated, not in my classroom avoiding the cafeteria, but at home in crowded apartments and small houses, avoiding the world.

I slowed down. For me, this was the hardest part. Giving up food and water was nothing compared to not being able to pull every weed, plant every seed, ride my bike up and down every last hill, walk the dog until blisters appeared on my toes. But sometimes it’s better to just stop for a moment, to let the world continue its craziness around you, to rest your eyes and your heart, trying to see the spinning from a place that is still.

Moment by moment, hour by hour, day by day, I made it through thirty of seventy-one days of quarantine without food or drink. And last night’s enchiladas and Libyan honeycomb bread, this morning’s strawberry-rhubarb pie and ice cream, this afternoon’s bike ride with my boys…

They tasted sweeter than you could ever imagine. Like winning the lottery of luck that is my life (because it is). Like putting that first bite in your mouth after a month of fasting, only that bite is Pure. Gratitude.

Because nothing in this life is more precious than what we love, what we long for. A taste. A drink. A relationship with our students, our families, our friends.

And in thirty days, you can truly taste how much joy longing can bring.

Ingredients:

Four months of news stories and 4,300 worldwide deaths.

Social media memes and accusations.

Schools filled with unimpacted children who put their hands everywhere.

Understaffed schools that can’t keep up with soap consumption.

Homeless and hungry children who find their only two meals a day here.

Immigrant children who come anyway because this is nothing like escaping extreme poverty and war.

Directions:

Preheat hope to 375 degrees. Maybe it will be hot enough to kill something.

Put every worry and frustration into the rolling out of dough. Tough and round, an imperfect circle, wide enough to cover the whole belly of the beloved dish.

Spin and skin the apples until they are nothing but spirals of juicy love, bittersweet and crunchy and soon-to-be-soft, soon-to-be-coalesced inside a cinnamony mix of something sweeter. More hopeful.

Slice slivers into the top crust. Each piece is a taste of our world, cutting out the healthcare most of us don’t have, carving lines into the economic burden, trying to cover up the death toll.

Place the pre-cooked apple concoction into the lower crust belly, its syrup soaking through the floury dough, waiting to be better.

One by one, lay the lattice. Say a prayer, ask for something better, hope to God this will come together perfectly in the end. One by one, lay the lattice. Take your time. Gather your patience. Think of your children. All of your children.

Press the two parts of the world together: the bottom crust which opens its arms to everything that will fit; the top lattice which opens its door for all the cursed steam to escape, to prevent overflowing, to make a perfect pie.

Bake your pie. Bake, bake, bake your pie. Know that, after the timer beeps, after you have scrubbed flour powder into the compost, after you have soaped the dishes, after your pie has rested on its stinging-hot shelf, everything will taste oh. So. Sweet.

Teach your students how to say “crust” before they bite in tomorrow, before you won’t see them for three weeks, before the actual Pi Day.

And hope for many more Pi Days with oh-so-many pies as perfect as this one.

i walk my puppy,

fight weekend grocery store crowds,

and bake a cheesecake

before 10 a.m.,

i cook raspberry compote

and finish laundry

by noon, i’m ready

to begin this Sunday cleanse

and climb out of here

the city beckons

(no, no—the world beckons

for another chance)

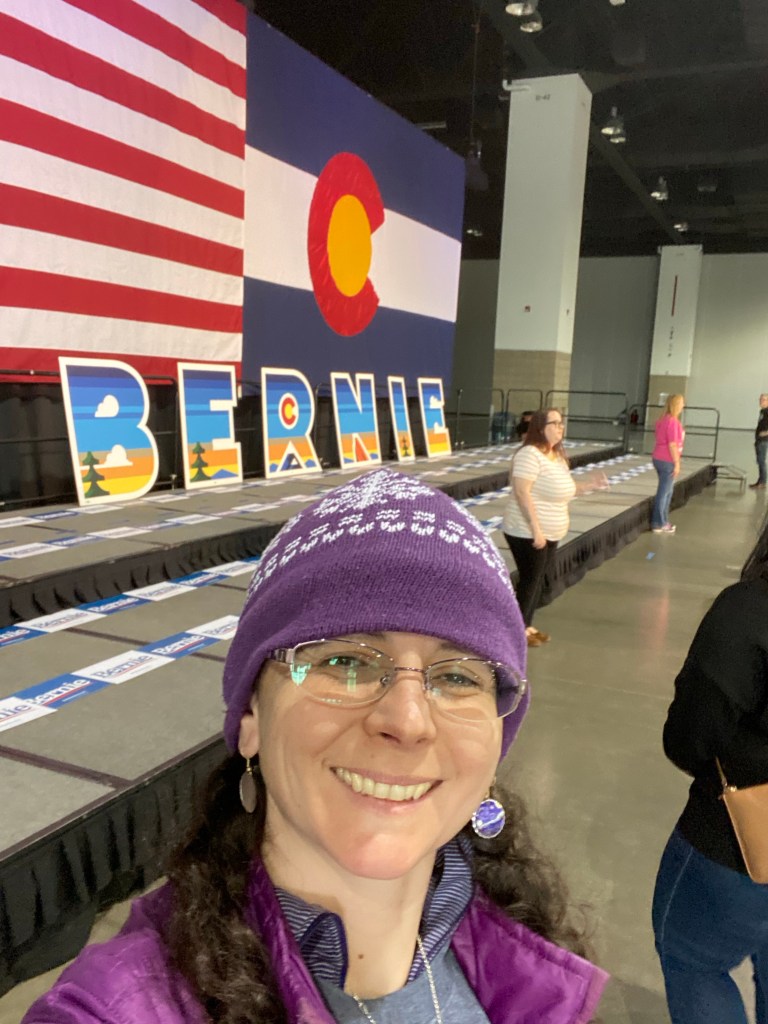

our democracy

and the fate of our future

rest with how we vote

(even though it’s cracked,

my daughter’s birthday cheesecake

is one of many)

let this election

be one of many chances

to give us all hope

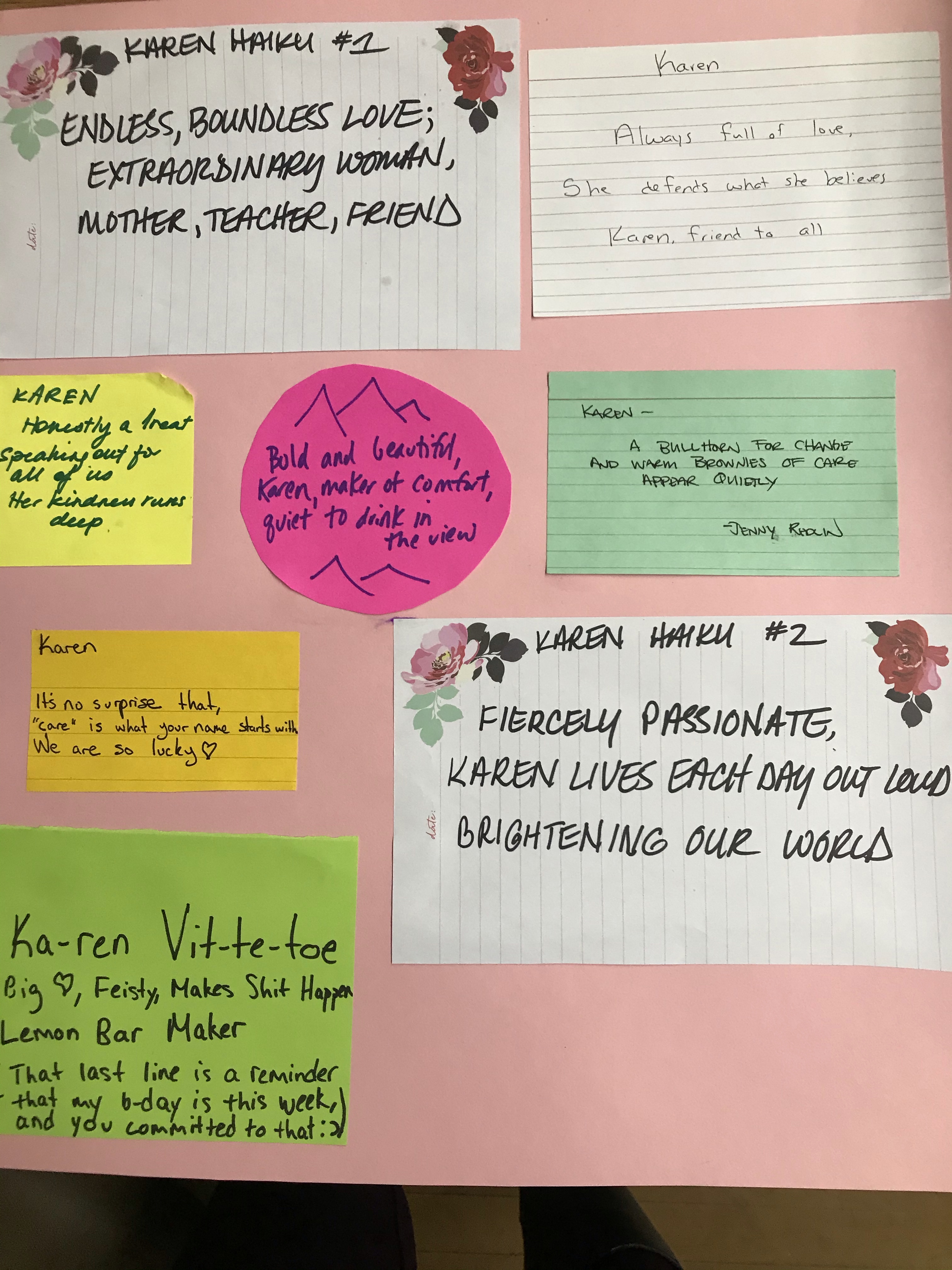

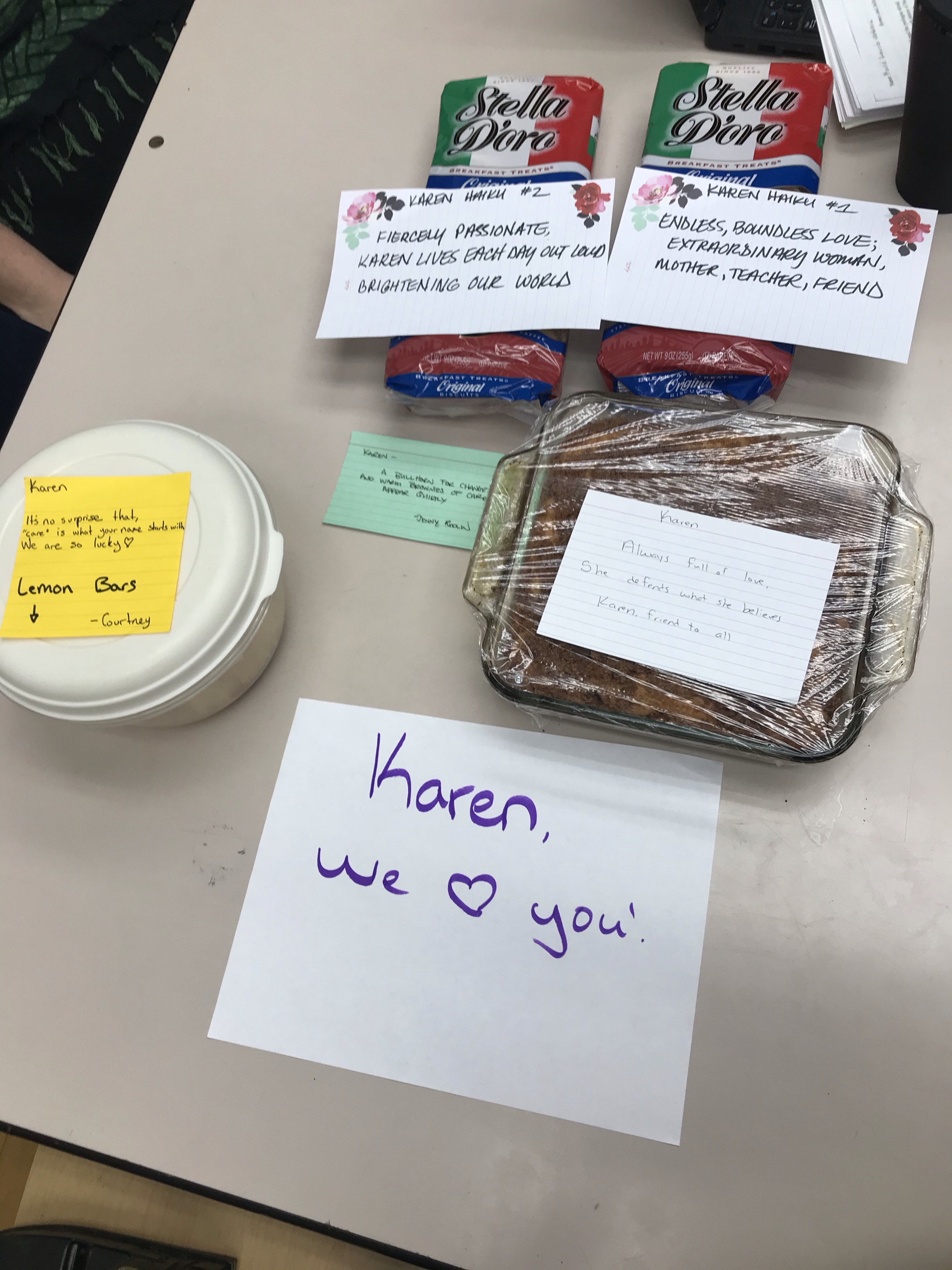

most don’t write for me

it must be a blue moon day

and i am so blessed

always pure of heart

she’s the sweetness in this cake

tres leches, thrice loved

our preparations

for this moment of our lives

go beyond torrejas

beyond this sweet sauce,

this Christmas stocking for you,

beyond this moment

our preparations

go beyond twenty-two years

when we were babies

when we were in love

as only the young can be

and he promised me

what promise, you ask?

to open our home with love

when it is needed

Most people who hear that I have three, not two, daughters, send me a sympathetic look, or trade empathic stories of their own three or four girls, or commiserate in some form or fashion.

“Three teenagers? All at once?” Their shock and worry for my well-being come hand in hand with the realization.

Rarely am I praised or labeled blessed for such a thing. Because three is too many. Three girls, or three of any one gender, is too many.

But an accusation is a whole other ballpark that I don’t quite know how to bat for.

“Can’t you understand the plight of my daughter, someone who doesn’t have two sisters who are her best friends, and how lonely she must feel? And you sit here with your sisters and have a house full of friends and treat her that way?”

She stands at my doorstep. I recognize her voice, but I find my feet paralyzed in the kitchen staring at the pizza dough my youngest has spent the better part of a day preparing. My youngest, who righteously defends herself against the bullied petulance of her sisters, but outside of our family, has likely never said an unkind word to anyone.

“Do you not like my daughter? Do you have the decency to admit it? And YOU, what did YOU say to her? What did you do to her?”

I listen to my girls stumble over words as I put the scene together in my mind. One neighbor came over and spent the morning rolling out cookie dough, boiling water, squeezing lemons, and stirring iced tea. She and my youngest set up the lemonade stand at the corner and made a catchy but annoying hip-hop rant to woo passing cars: “Lemon-ade and cookies too, get your lemon-ade, doo-doo!”

After more than an hour and many dollars later, the pitchers of iced tea and lemonade were nearly empty before the third child arrived. My middle girl and I were still in the midst of the nightmare job of pulling tiny bits of crabgrass out of five hundred square feet of pink rocks, and my oldest had just pulled up with a shake and chicken nuggets, her hair freshly cut, offering everyone a taste.

The third girl stood at the edge of the scene, and Riona offered for her to help clean up, giving her two cookies and five dollars once the lemonade was gone.

“I want to know who called my daughter anus? Was it you?” I can feel her eyes burning into Riona’s, whose tears are already burning down her cheeks.

“We were just messing around. We say that to each other all the time,” the first friend pipes in.

But she is not done ranting. She lays on the (must-be) Catholic guilt of her daughter coming home crying, of being excluded, of the disgrace of the name-calling, pinning it directly on this household and “the fact that we know nothing about you three girls even though we’ve spent so much time with ___, and nothing like this has happened before.”

The snake that is Jealousy has slithered heavily down the block, consuming all air from my lungs, from my children’s stuttered responses, and choked us all into shocked silence. How venomous it tears apart a young girl’s heart, how twisted offhand remarks become when in the presence of new friends.

I begin to find footing to approach the mother, but she has stormed off before I can peel myself from petrification in my pocket-door kitchen.

Did she not take a moment, in her Mama-Bear attack, to think that it might be possible, just maybe, that her girl was feeling left out and blew the comment out of proportion? Did she want to find a scapegoat for the tears? Did she want her to lose a friend?

Tears are the only characters in the room once she leaves. Everyone has her version.

“She thinks we’re friends with each other?” the sisters exchanged snarky glances.

“I just offered her some of my ice cream.”

“I was weeding.”

“I gave her five dollars and a cookie.”

“I called her anus like I do every day, and I am NOT playing soccer with her no more.”

And what is a mother to do?

I present my Jealousy Lecture, fresh from my pocket and a conversation with my oldest from just a few days ago. “Just think how you feel when your sister gets something that you don’t, and how hurt you are, thinking that we favor one of you over the other one.”

Everyone nods, recollects, brings fresh tears to her eyes as they draw upon recent memories of Air Pods or Apple Watches or a damn raincoat two sizes too small and three years past being angry about.

But they get it.

“Why don’t you two make a card…”

They take the card stock, the permanent markers, the classroom supplies I am always buying for my classroom, and blatantly apologize as only children can: “I’m sorry you felt discluded.” “I’m sorry I called you anus.” “You are our friend.”

Too afraid to walk the block alone, I accompany them to the house. They timidly ring the bell, and the mother answers, her husband hovering in the doorway.

Perhaps the mother says something. Calls her daughter. Perhaps there is a vague apology to me for storming in and accusing my girls of something that they didn’t say.

But no one hears anything but his voice. Threatening. Thick with hatred. Eyes on the friend. “Don’t you EVER say that crap to my daughter again, do you understand me?”

I can almost feel the fist in his voice. The toxic masculinity as he repeats the command as if he is speaking to an enemy in the ring, a wife who won’t listen, a waiter who brought him the wrong drink.

Tears immediately fill her face as she backs away, unable to even speak the words of her apology to the young girl whose parents believe everything she says and have no idea how to handle any of it.

Riona puts her arm around her for the long block home, consoling her, telling her it’s not her fault.

In the retelling of events, Izzy asks, “Is he like that angry customer who tried to get us all fired for asking him to check the freezer for the pint he wanted?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

“Is he like that guy who cut you off and flipped you off?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

“Is he like Trump?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

And… I don’t have to explain. They already know, though no men in their direct life are anything like these men, and no women in their life would accuse without taking the time to understand.

They enter, finish baking the pizza with the fresh-snipped basil and spinach from the garden, set up the hammock to eat it in, sit in the swing together, play Scattergories and act like best friends… if only for a couple of hours.

At least one of today’s accusations can have some validity.

At least I don’t need a sympathetic look for how I have raised them. How lucky I am to have a man who has never spoken a harsh word to anyone, let alone an 11-year-old girl.

And at least they know how to make lemonade out of lemons.

strawberry rhubarb

can’t save our relationship

no matter how sweet

i’ll have to find words

to fill the lattice loopholes

between bites of love