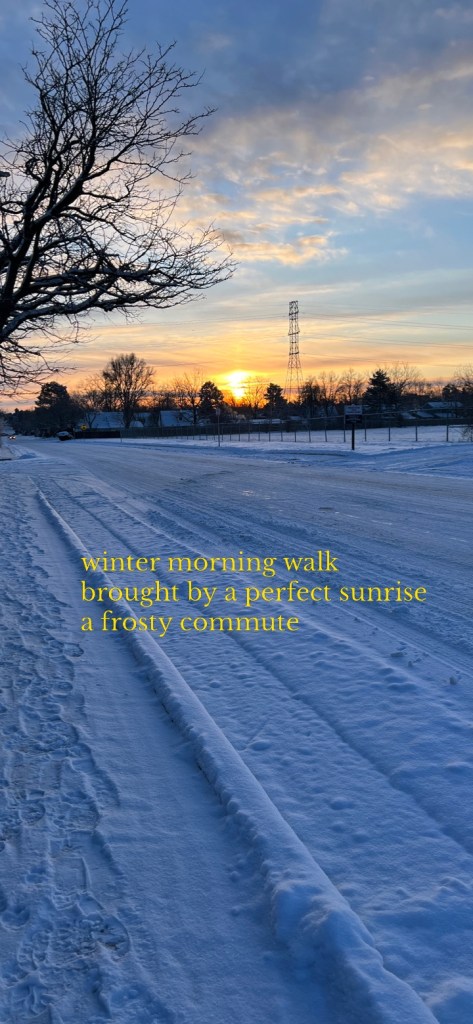

After the funeral, we stand on the side of the road, the airport train bulleting past as January exposes itself in its bitter, beautiful glory: soft flakes fall from the silent sky, casting a quiet shadow on the muffled wails of all the mourners.

After the funeral, I hug a few former students and a few current ones. I praise one for his brief eulogy, ask him what he’s doing now. “Working, Miss, always working.” My current student scans the crowd for the other teacher who came here today, searching for a hug, for a morsel of hope.

After the funeral, I drive across slick streets to my parents’ house which is halfway between the mortuary and my home. We sit for hours discussing everything from senseless acts of violence to my children’s future to an upcoming family vacation.

After the funeral, I come home to my husband, fresh off his on-call work, and hear about his morning of installing and repairing fiber optics. My girls are all gone, one at college, one at work, one at her boyfriend’s house. The house, looking out on the snow that keeps falling from the sky but won’t cover the streets with its quiet beauty, feels empty, lonely, and just. Wrong.

But… I still have my life after the funeral. I still have all three girls. My husband. My country. My culture. My home. My place in this world.

I didn’t travel across half of Africa and then all the way across the world to save my family from a civil war so that they could have a better life, only to lose my eldest child to American violence years later. I didn’t leave behind my ailing mother, my grandparents, my religious practices, my native foods, the soil under the house I built.

And today, the snow seems hopeless. It doesn’t bring me the renewal that it usually brings. It doesn’t feel like a new beginning when a family so close at hand has been stripped of every new beginning.

A young man. A student. A basketball player. A brother. A son. A grandchild. A caregiver.

They were only allotted two hours in the mortuary. The line of people never stopped for the duration. The door never closed. With every seat taken, bodies had to line up and down every aisle, along the back of the room, along the front of the room, blocking the windows, next to the casket, sitting on the floor, holding small children in laps, comforting babies, comforting wailing women, trying to find comfort.

All four surviving siblings spoke, their voices cracked with a painful mixture of grief, anger, and remorse. And then they opened the mic, and we all stood as one after another human–former teammates, church leaders, cultural elders, friends, classmates, aunties, uncles, cousins–got up to repeat the same message: Giving. Kind-hearted. Generous. “Give you the shirt off his back.” Loving. “My best friend.” Funny. Down-to-earth. Direct.

All the qualities you’d want in a person, a friend, a son, a brother.

We could have stood there for eight hours, but the time was limited, the mic dropped, and the wailing women crept their way out into the snow.

After the funeral, for as long as I live, I will carry her guttural clench of despair in my ears, my heart, my memory. The sound of a mother, bent over her son’s open coffin, crying out to God and all of South Sudan and all of America and all of us: “Why? Why must I bury my son?” Heard not in words but in sounds, deep, unearthly sounds escaping from the depths of the hell that she is living in right now.

After this funeral, I will never be the same.

I have spent most of my adult life trying to welcome these immigrants into a country that robs them of everything. Even life.

After the funeral, no matter how horrible I feel about the hopelessness that is America, I will never, ever feel the loss that she feels: so profound, so innate, so impossible to overcome.

So impossible to overcome.