The suits came by this afternoon. We were in the midst of discussing our fears, which in a Newcomer classroom involves many pictures, much acting out, my modeling of three circled fears, and quite a bit of screaming along the decibel lines so that they could understand the subtle differences between a little scared, a lot, and TERRIFIED.

These fears would go into their Bio Poems, every English teacher’s favorite go-to poem, which seemed so much easier during my last fifteen years of teaching and seems ever-so-complicated now that I have to find emojis and facial expressions to visually demonstrate a range of emotions from happy to angry to guilty for line six, “Who feels…(list three emotions) today”.

The suits heard me scream. They peeked over the students’ shoulders for the entirety of their five-minute, who-knows-why visit. They thanked me in their usual ever-polite way and walked towards their next classroom visitation.

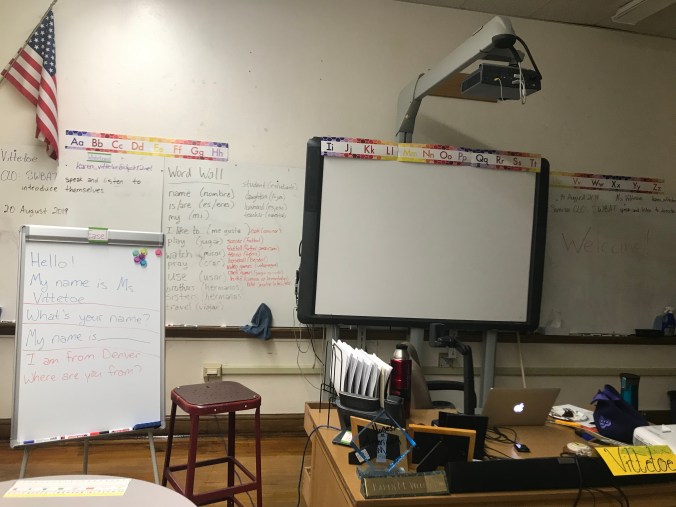

We get a lot of visitors. A white woman just like me and nothing like me wrote a book about our Newcomer Center, and everyone now wants to partake, to drink in her words, their struggles, and culturally tour what it’s like to learn English when your background is anywhere from illiterate in your native language to I-understand-everything-Ms.-says-but-refuse-to-verbally-communicate.

To simplify fears, I asked my students to circle their top three from a photo-supported list of superstitions, animals, insects, arachnids, the open sea, death, crowds, public speaking.

“Are you afraid of dogs?” I asked one, trying not to laugh.

“No…”

“Say the whole sentence now.”

“No, I’m not at ull uf–ry–eed of dogs” came the reluctantly-read reply.

“Are you afraid of spiders?” I asked another.

“Yes, I’m terrif-eed of spee-ders.”

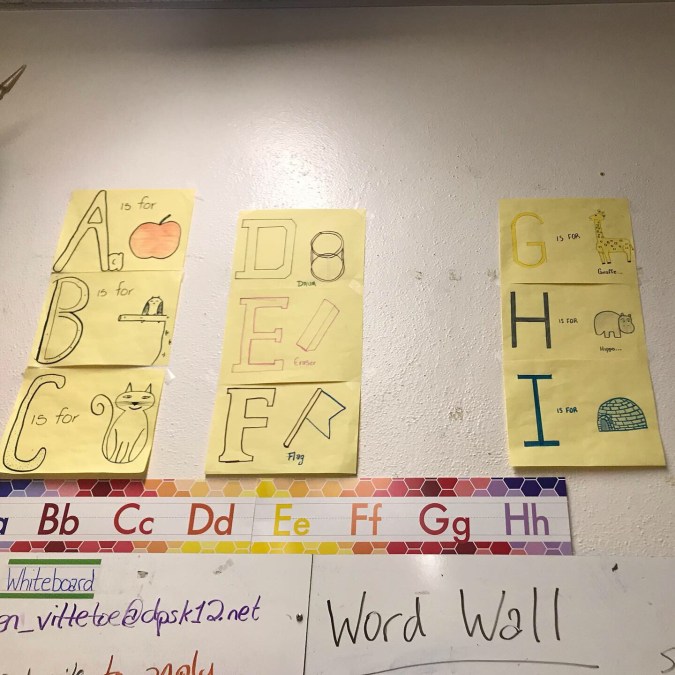

With every sentence comes a retracing of steps, a pronunciation clarification, a pointing to the word, the picture.

And with every sentence, their silent fears hung in the room waiting for the words they don’t yet know to formulate in their minds. More than death, more than the open sea, more than flying or walking under a ladder.

They fear those adults walking into our room. What are they looking for? They fear they will never see their homelands, their aunts, uncles, grandparents, ever again. Some fear they’ll never see one or the other or both parents, the ones they had to leave behind. They fear the next school year when they’ll have a full-on regular schedule and “grade-level work, as all students deserve rigor” and won’t be with me or each other for the majority of the school day. They fear their citizenship status, their asylum status, their social status in a country too complex to summarize in a few Thanksgiving lessons.

Am I imagining these fears? Am I putting words into their mouths, thoughts into their heads?

And this was just one line of our poem.

It took us two hours to write a ten-line, sentence-framed bio poem. The suits didn’t see the real struggle, the re-explanation of vocabulary such as siblings, daughter, What I miss most… They didn’t see how easily some students filled in the blanks, how carefully others penned their cardstock, how reluctantly they read aloud their poems to their partners.

They didn’t read the lines that could break their hearts. So simple, language. So complex.

In five minutes, in ten lines, in two hours, could one write a life story? Could they insert their biographies into the blank spaces so that we could all understand where they’re coming from? Could they explain to me, to the world, the fears that they carry?

No. Bio poems aren’t enough. Suits visiting for five minutes is not enough. This post is not enough.

Only their words, their many, many words in so many languages hidden behind these lines, and their faces, their multi-colored, multi-emotional faces, could begin to capture what is missing from their words.

But the suits didn’t stay to see any of that. I hope that you will stay. I hope that you will see them for who they are and not just peek over their shoulders, unaware. I hope that you will listen and take their fears right off of this page and into a better future.

I hope that you will take their fears, your fears, all of our fears, and turn them into something more than words. Something powerful. Something that we can shape into a better bio poem for all of us.