humanity

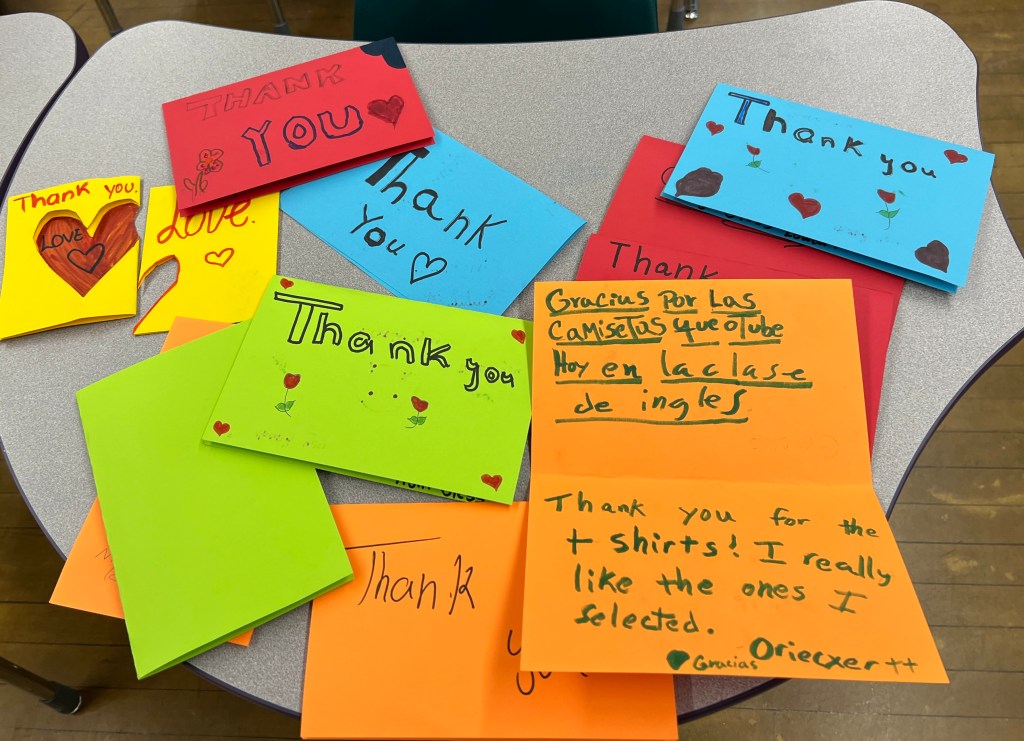

Thank You (In Every Language)

There aren’t enough words, in English or Dari, Pashto, Spanish, Arabic, Tigrinya, Romanian, Swahili, Kinyarwanda, or the twenty-three languages of Guatemala, to express my gratitude today.

Today was EXHAUSTING. It started with the first time this semester that I drove my car to work. Yes, I have been walking in the snow and ice that has stolen Denver’s mild winter this season. Yes, I have ridden my bike all of seven times. No, I haven’t driven my gas-guzzling car even once.

Until today.

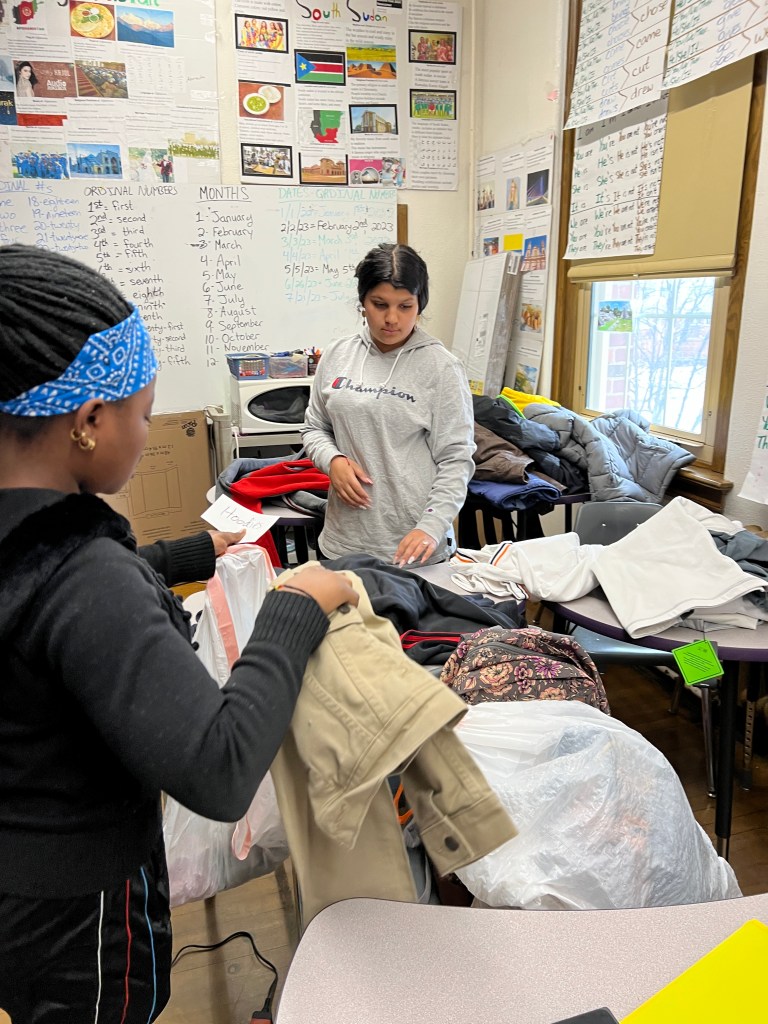

It was supposed to snow today (again), so it was a good day to drive. My eight-passenger car was filled to the brim with clothes you gave to us.

My colleague, my two daughters, and several of our students marched back and forth from the long sidewalk of our 100-year-old school to the parking lot. Back and forth, breaking our backs, to bring this to them. My colleague and I spent the entirety of our ninety-minute planning period sifting through and organizing the clothes, planning a lesson that should have happened three months, three years back… but there is so much to teach them in the time they put their faces in front of us. From the only-in-English auxiliary verb ‘do/does’ that exists in nearly every question and EVERY negative answer to how to navigate our complex transportation system to how to cope with the fact that they witnessed a pregnant woman murdered in front of them in the Kabul airport and don’t know how to calm their nerves for three hours with me every day.

But they find a way.

We find a way.

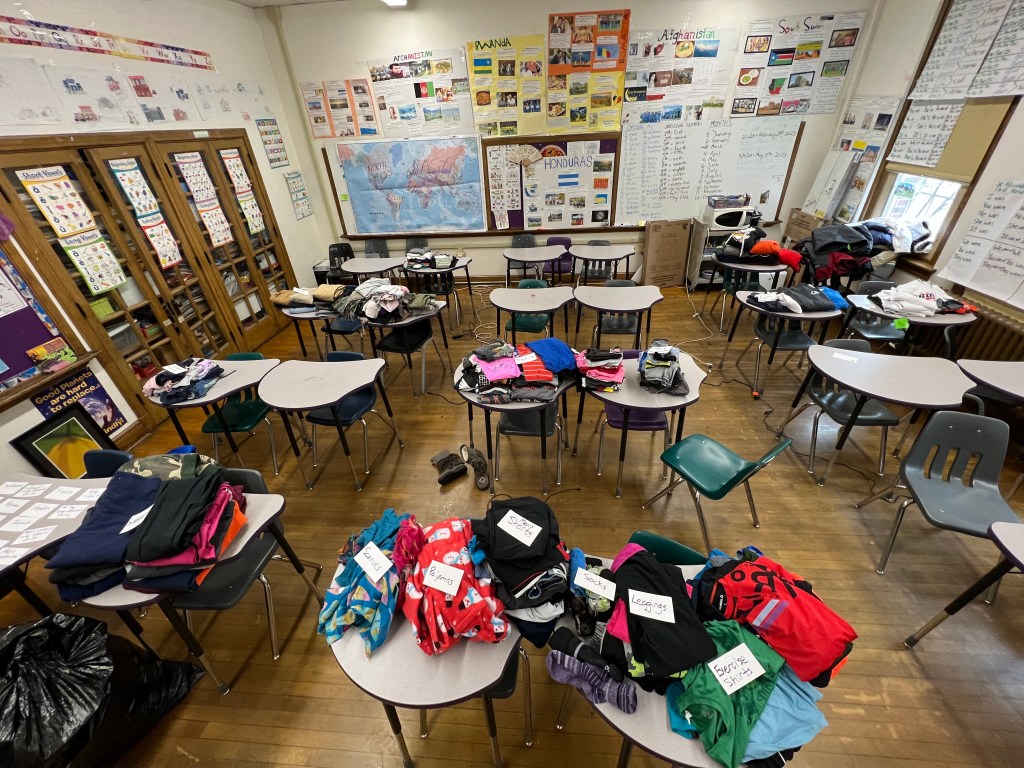

Today’s way was labeling the piles with notecards and making copies of said cards for these students to pick up as they walked in the door.

“Let’s continue to practice with present-tense verbs. What clothing do you need? When I say you, I mean your whole family. For example, you could answer, ‘I need exercise shirts’ or, ‘My brother needs hoodies.'(always an emphasis on that final ‘s’)”

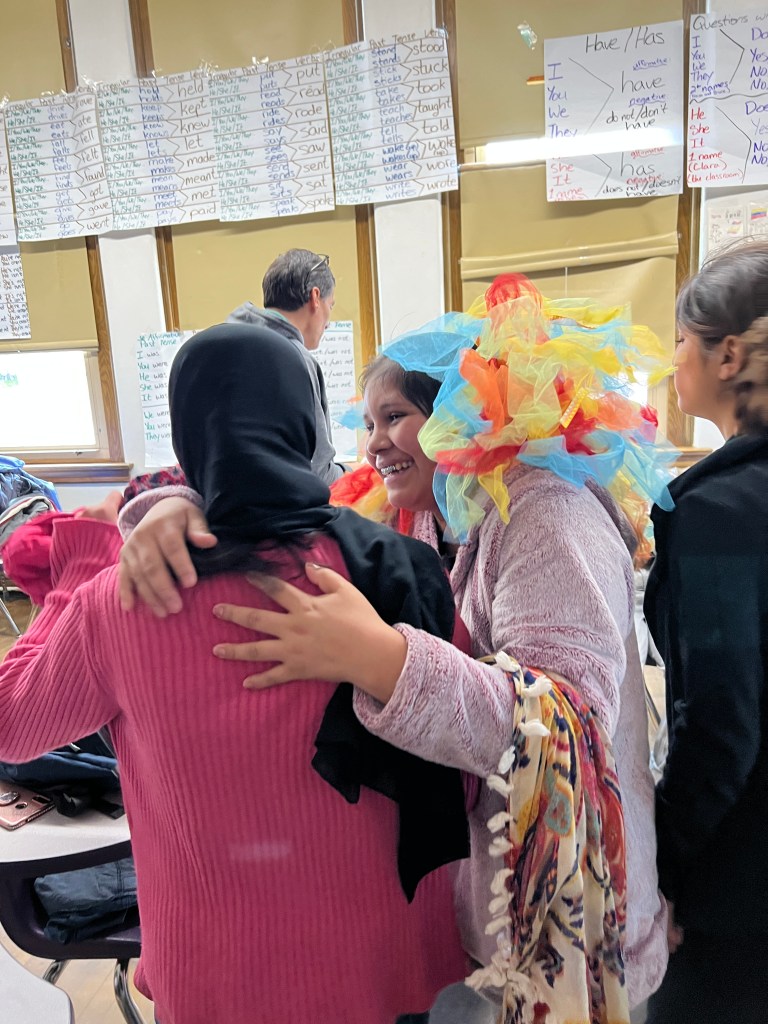

They held up their cards. They looked around the room at the piles of clothes that surrounded them. They asked their paraprofessional interpreters what the words meant. What this day meant. What craziness, what generous craziness, lay before them in perfect piles.

And they recited their sentences. They practiced their English. They learned what a hoodie was. The English word for scarf. For long sleeves. For T-shirts. For little brother (there was an entire bag of clothes for little brothers; another for little sisters).

I met you twenty years ago, my friend, in my first nightmare year of teaching. When it was so hard and they crammed thirty-eight of these kids in my room and I didn’t know if I could handle it, and you stayed at that high school way longer than me (I gave in to pregnancy rather than facing it), but ultimately you left the profession. Yet I know your heart is still there. Your heart is still here with me in this classroom of Newcomers.

You gave me a lesson today, you and your friends and your book club and your kind-heartedness.

You gave us a lesson today: in English vocabulary–everything from learning the names of clothes to how to write a Thank-you card (“Miss, what is this ‘Dear’ meaning at the beginning?”) to what it is to be human.

And it’s in all their faces. Their joy. Their gratitude, their hope in an America that you have given to them today.

Thank you. Gracias. Mulțumesc. شكرًا لك. له تاسو مننه. متشکرم. የቕንየለይ. Asante. Murakoze. Thank you.

Soft Cat, Calm Night

Ode to Winter

For You, For Me

hospitality:

the heart of an Afghan home

(how sweet the tea tastes)

Road Trip 2022, Day Three: Kentucky Creekside

Kentucky kayaks

have defined my sister’s life

this past fifteen years

through all the algae

fighting through climate crises

we keep paddling

life is a rope swing

make a running circle out

and don’t hit the tree

those just-jumped-in grins

can win our independence

from a dark future

Breathing Through

June: a harried month

with all the joys and sorrows

that make up this life

Tomorrow Morning

My husband finishes work at 16:00, but he invited me to dinner in the cool uptown neighborhood where he works tonight. Because he had to “flip a switch”, as the four of us girls teased him, at exactly 18:00, and he couldn’t be late.

And we won these smiles.

Someone with a camera (my camera) took our photo. A nice white woman with a GoldenDoodle sitting next to us. On a Tuesday in May that should have been eighty degrees but it was only fifty and threatening rain.

Threatening.

But it wasn’t a real threat. It wasn’t an 18-year-old one of my students who walked into an elementary school in Texas to kill three teachers and EIGHTEEN 2nd-4th graders.

Nope. That life, that teacher life, is for tomorrow morning.

Tomorrow morning, I will rise at dawn, or just when the bluejays call me awake. I will walk my dog two miles through my Denver neighborhood. I will kiss my blue-collar husband goodbye and let my baby daughter drive me to the high school where we live/work. And we will walk into the Italian-brick-National-Historic-Monument of a high school and pretend that we don’t know the kid who could walk into an American gun store and kill the next generation in ninety minutes.

And I have worked for twenty years in this profession where my heart breaks every GODDAMN DAY in an attempt to keep that kid from doing that.

And you know what?

Tomorrow morning, I am going to see my recently-arrived refugee students who spent thirteen years on a list or thirteen harrowing months waiting in line or thirteen lifetimes waiting to come to the savior that is America, and try to explain to them, in my broken Dari/Spanish/Arabic/Pashto… that we are just as broken as them.

Tomorrow morning, I will rise at dawn after a night without sleep, and I will be there for them, trying to convince the boys that the gun store doesn’t exist and the girls that they have a future that includes educational advancement, no forced marriages, and a life that they can create.

And look at my girls.

Just take a look at the three girls I have raised who have to face this.

Tomorrow morning.

And Biden, you’re going to give a speech? And Governor Abbott, and Donald FUCKING Trump, you’re speaking at the NRA convention this Friday, I hear?

And what the FUCK are you going to say? Thoughts and prayers?

Are you going to be there tomorrow morning, when the blood of eighteen elementary students is still staining our hands? Are you going to walk into that high school tomorrow morning, having that conversation with the kid whose negativity has walked him into the free-for-all, no-accountability gun store that is our nation? Are you going to sit by my side tomorrow morning as I try to make it through another day in a profession that vilifies and disgraces me with false promises and broken souls? Are you going to tell my Newcomers tomorrow morning that this really is the American FUCKING Dream?

No. You are not.

Tomorrow morning, before the alarm goes off, I will be awake. I will take my broken salary, my broken heart, and I will hug my kids. The only gun I will carry, the only bullets out of my mouth, are these words:

I am here.

I am here now. I am here later. I am here tonight.

I am here for you. For a million years.

And I will still be here for you.

Tomorrow morning.

Ravine

My mother once fought a ravine and two strange men, and only a woman could tell you which was scarier. The dusk settling in on a rural New York night, a 30-something woman trying to maintain her health with a long walk, and a pickup truck.

Doesn’t every American nightmare begin and end with a pickup truck?

You can feel the humidity in your mouth. As thick as gnats, as thick as a cloud of mosquitoes fighting for blood. Hovering in the clouds that are the sky of the upstate, the Finger-Lake country, the I-can-get-away-with-this country. Choking you.

Telling you just what your mother told you—that you should have stayed home. That you shouldn’t have gone to college. That you should have been a housewife. That education and careers are for penises. That you aren’t really a woman if you aren’t surrounded by a cartload of kids.

And you. She. Didn’t listen. You took that 2.5-mile walk in the dusk, running your long and delicate fingernails along the cattails. Feeling that soft moisture in the air, filling your lungs with droplets as golden as the fire from the sun. Feeling your freedom of marrying a man who would never in a million years tell you not to be who you are. Just letting you.

Walk.

Walk that walk. Walk all the way around the “block”, the upstate block that stretched between a cemetery, an elementary school, houses built two hundred years back, and cornfields flooded with the life of early summer, ready to burst with golden morsels of joy.

She will tell you this story later (not much later). You are nine years old, sitting in your stone-floor kitchen, listening to her tell it.

It is the same story she told you years ago, about her mother writing the letter to the college and telling them that her daughter shouldn’t go, that women are housewives, and why would she waste her life on an education rather than raising babies?

But there’s a ravine in this story.

A ravine. Resting above Flint Creek, the creek with the black snakes in summer, the creek that freezes so hard in winter that we bring our toboggan and sled right down over its ice, the creek that is a mystery and a blessing and a danger all wrapped in a childhood built upon the backbones of exploration.

In case you were wondering, this far along… the ravine saved her.

She clung to the vines, the grass, the weeds, the green growth along the banks of that creek as if her life depended on it.

Her life depended on it.

Because on her 2.5-mile walk, at dusk, in midsummer, two men followed her and did all the things two men in a pickup truck do.

They drove forward and circled back. They blasted their radio and their diesel. They shouted and slurred.

And my mother won a full-ride scholarship for that nasty letter her mother wrote in 1972. It was the Women’s Liberation Movement, and goddamn it if someone was going to tell her or anyone that she wasn’t going to get her degree. Even if it was her mother.

And she clung to the side of that ravine, hiding her waist-length auburn curls and her 120-pound soul and her fear, until she heard that diesel drive away.

And she didn’t call the cops or cry or call my father.

She walked home and told us, my sister and father and me, the story.

And that is why I am here today, writing this.

Because she clung to the terror and came out on the other side and didn’t get raped.

And how fucking sad and amazing and heartbreaking is that ravine, that ravenous victory?

How fucking sad is that ravine?

For Kevin

Dear Family,

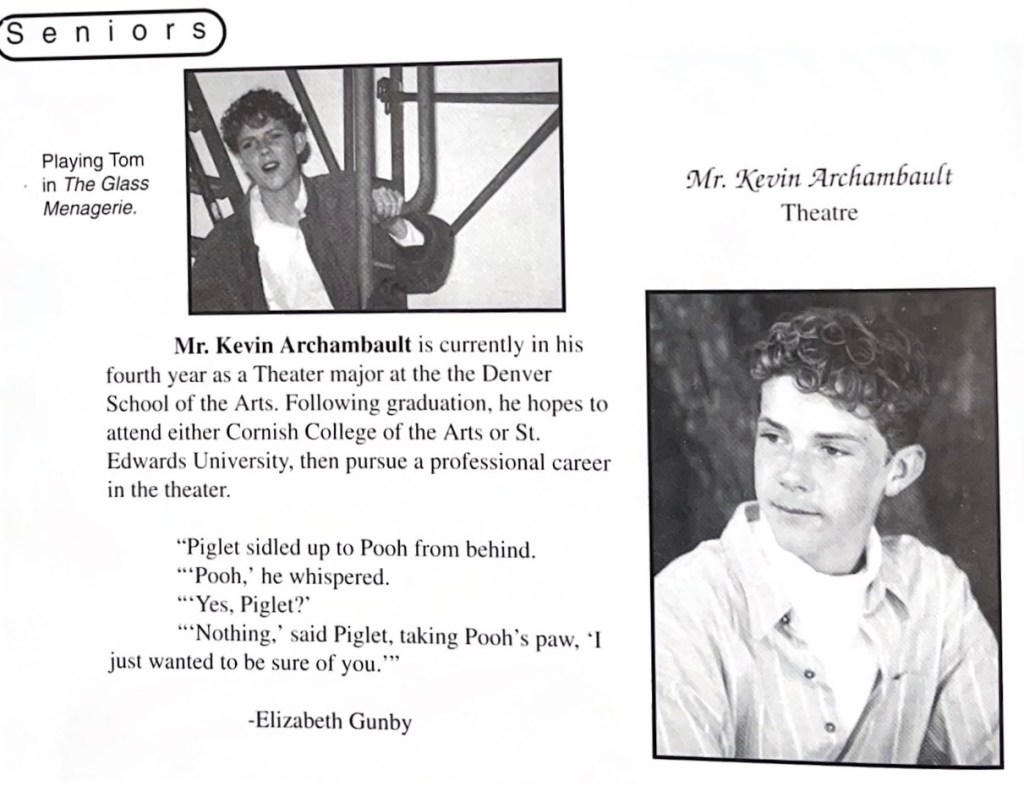

It would be impossible to encapsulate in words Kevin’s indelible impact on everyone he met in life. I was lucky enough to know him as a young man—really a fearless, jubilant boy—who knew how to bring vivacity into every room. Below is an entry from my personal journal written when Kevin was about to graduate from DSA.

*******************************************************************************************

Thursday, 13 April 1995

It was Kevin and Hart (DeRose)’s senior showcase, a play called “On Tidy Endings” that the two of them wrote, directed, designed the set of and starred in. It had only two other minor characters, Wes (Zelio), and Elizabeth Horwitz. It was the story of a man who had died of AIDS, and it had Kevin playing his lover and Hart playing his ex-wife.

Their confrontation in his boxed-up apartment. I will never be able to even begin explaining how powerful that was, so I won’t even try. Let me just say that it was the best performance ever at DSA, and the best performance I’ve seen anywhere—on TV, the movies, or the theatre—since I first saw Dances with Wolves.

Kevin has grown up so much that I almost can’t believe he’s the same person I saw four years ago dancing a South Pacific scene with a hula skirt and coconut breasts. Kevin. I cried at the end, first for the characters in the play—their lives, their pain—it all affected me so much. And then I cried because I realized all too quickly, all at once, that he’s leaving, that soon the first graduating class of Denver School of the Arts will be gone, that soon that will even be me, me having to say goodbye, and now they’re leaving, and everyone leaves, and it hurt so much, but it was a good hurt, a cry that was filled with laughter and smiles, tears that were filled with hope and pride.

Standing ovation and then a room full of sniffling noses and unquieted sobs, everyone hugging each other, everyone loving each other like family, like a family that could never, by any means, be torn apart. I could not stop the tears from flowing down my cheeks for a long while, not until after we all eventually shuffled into the community room, not until after I hugged Cheryl and met Tad, not until after three glasses of punch and a piece of cake, not until after I hugged Devin, not until after Kevin signed my program, not until after talking to Olivia about senior year, not until after the toasts of many loved ones, not until after the pain of losing became the everlasting hope of gaining.

*******************************************************************************************

Kevin will always have a place in my heart. He was a genius in every way—through acting, writing, singing, and, most importantly, loving. He loved everyone in his life, and he will always be loved. I feel so fortunate to have known him and shared so many moments of joy and sorrow, whether we were out to lunch at the back booth of Pete’s Kitchen, sharing a shake at Gunther Toody’s, dancing in Cheryl’s living room for her sweet sixteen, or singing all the songs we ever knew while riding in a horse carriage downtown.

Every memory is sweet, precious, and filled with love. And I will cherish him forever.