immigration

Thank You (In Every Language)

There aren’t enough words, in English or Dari, Pashto, Spanish, Arabic, Tigrinya, Romanian, Swahili, Kinyarwanda, or the twenty-three languages of Guatemala, to express my gratitude today.

Today was EXHAUSTING. It started with the first time this semester that I drove my car to work. Yes, I have been walking in the snow and ice that has stolen Denver’s mild winter this season. Yes, I have ridden my bike all of seven times. No, I haven’t driven my gas-guzzling car even once.

Until today.

It was supposed to snow today (again), so it was a good day to drive. My eight-passenger car was filled to the brim with clothes you gave to us.

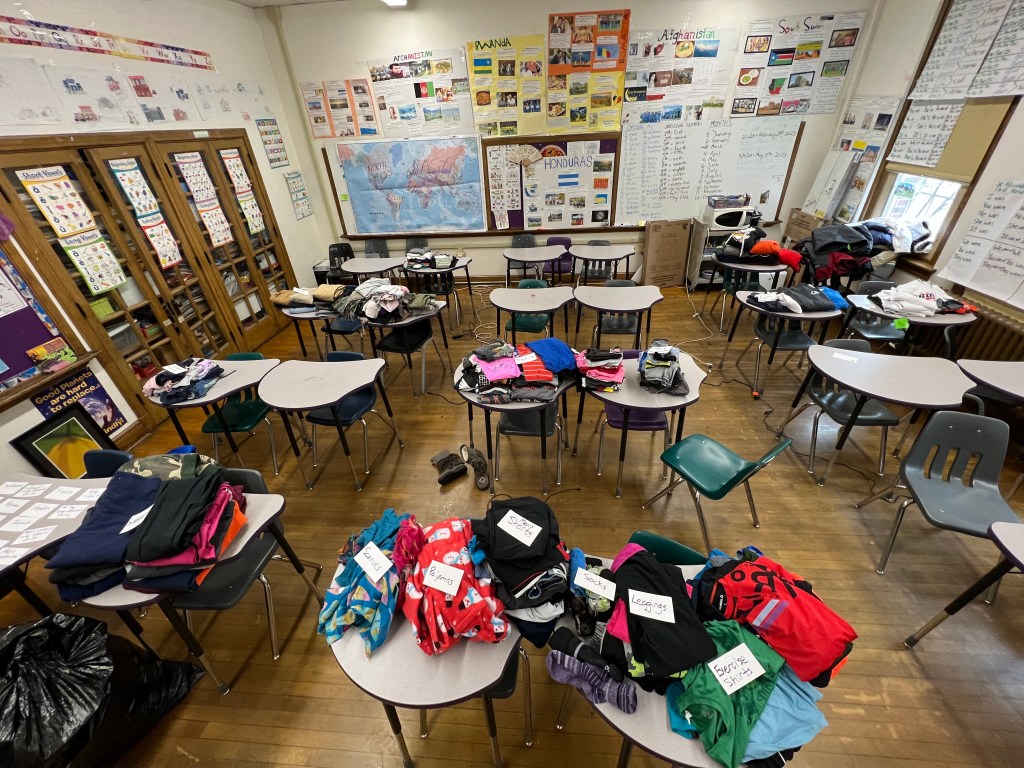

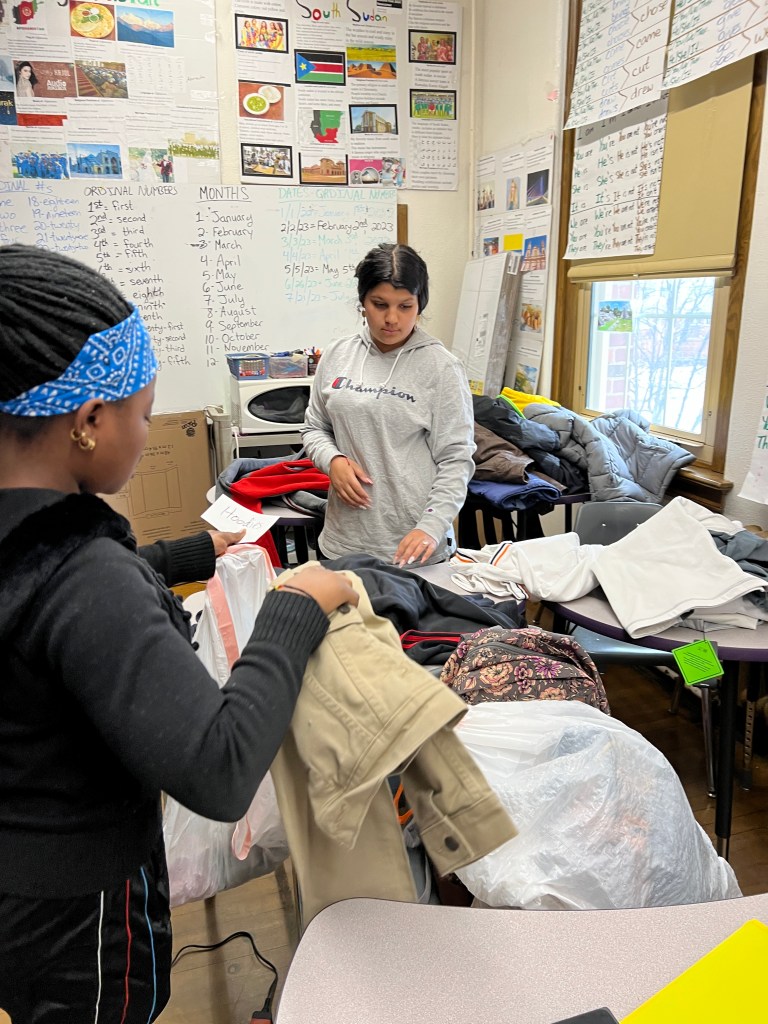

My colleague, my two daughters, and several of our students marched back and forth from the long sidewalk of our 100-year-old school to the parking lot. Back and forth, breaking our backs, to bring this to them. My colleague and I spent the entirety of our ninety-minute planning period sifting through and organizing the clothes, planning a lesson that should have happened three months, three years back… but there is so much to teach them in the time they put their faces in front of us. From the only-in-English auxiliary verb ‘do/does’ that exists in nearly every question and EVERY negative answer to how to navigate our complex transportation system to how to cope with the fact that they witnessed a pregnant woman murdered in front of them in the Kabul airport and don’t know how to calm their nerves for three hours with me every day.

But they find a way.

We find a way.

Today’s way was labeling the piles with notecards and making copies of said cards for these students to pick up as they walked in the door.

“Let’s continue to practice with present-tense verbs. What clothing do you need? When I say you, I mean your whole family. For example, you could answer, ‘I need exercise shirts’ or, ‘My brother needs hoodies.'(always an emphasis on that final ‘s’)”

They held up their cards. They looked around the room at the piles of clothes that surrounded them. They asked their paraprofessional interpreters what the words meant. What this day meant. What craziness, what generous craziness, lay before them in perfect piles.

And they recited their sentences. They practiced their English. They learned what a hoodie was. The English word for scarf. For long sleeves. For T-shirts. For little brother (there was an entire bag of clothes for little brothers; another for little sisters).

I met you twenty years ago, my friend, in my first nightmare year of teaching. When it was so hard and they crammed thirty-eight of these kids in my room and I didn’t know if I could handle it, and you stayed at that high school way longer than me (I gave in to pregnancy rather than facing it), but ultimately you left the profession. Yet I know your heart is still there. Your heart is still here with me in this classroom of Newcomers.

You gave me a lesson today, you and your friends and your book club and your kind-heartedness.

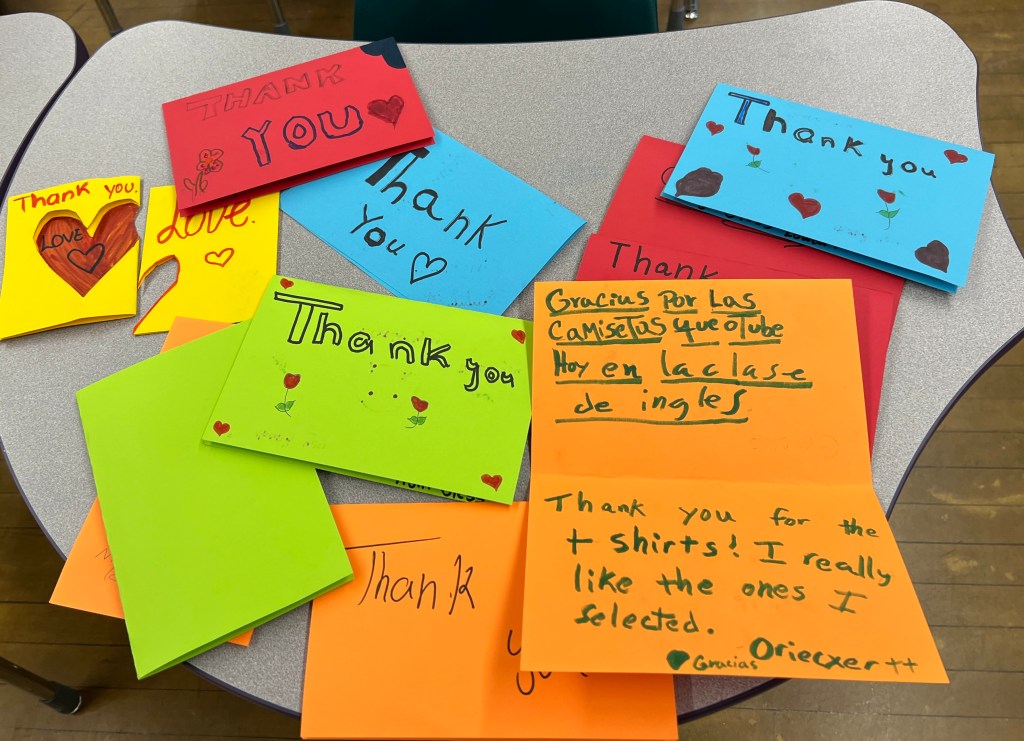

You gave us a lesson today: in English vocabulary–everything from learning the names of clothes to how to write a Thank-you card (“Miss, what is this ‘Dear’ meaning at the beginning?”) to what it is to be human.

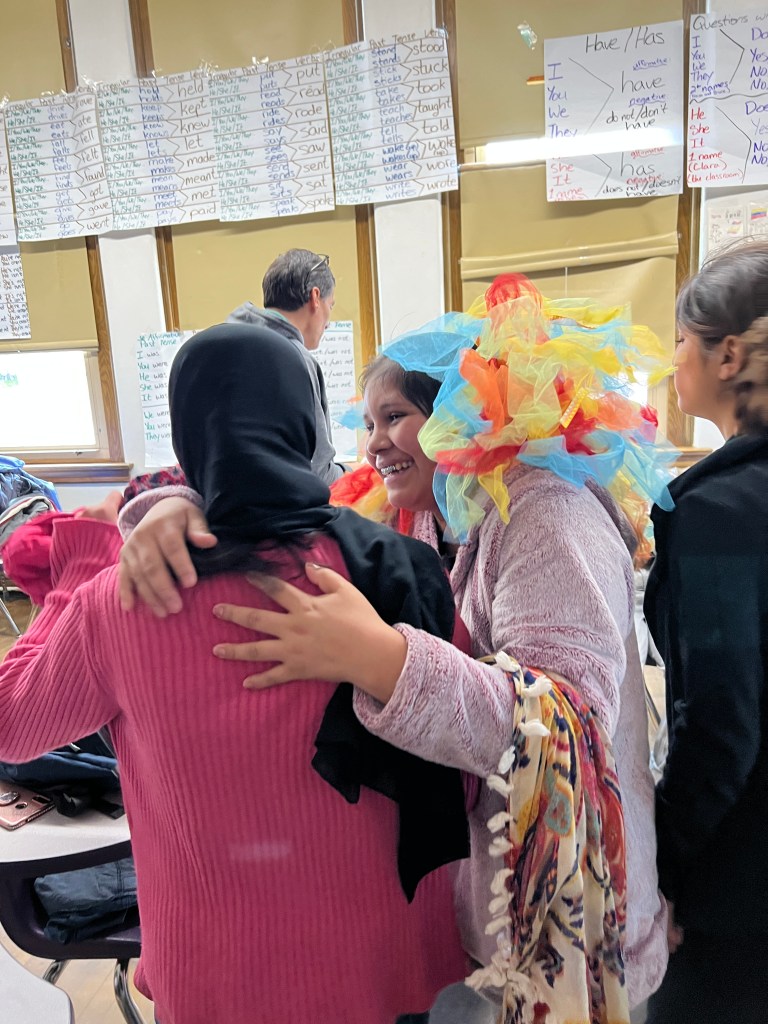

And it’s in all their faces. Their joy. Their gratitude, their hope in an America that you have given to them today.

Thank you. Gracias. Mulțumesc. شكرًا لك. له تاسو مننه. متشکرم. የቕንየለይ. Asante. Murakoze. Thank you.

Who Are Newcomers?

Who are Newcomers?

Newcomers are children who were forced to flee to the U.S. because their parents, their war-torn country, or their extreme poverty forced them to. Newcomers are children who chose to flee to the U.S. and crossed beasts and borders to do so. Newcomers are recent immigrants with a past–sometimes traumatic, sometimes dangerous, sometimes grief-stricken, but always vivid, powerful, and haunting.

Who are Newcomers?

Newcomers are children who lost months or years of education. Years of no delicious books, of playground antics, of kind and knowledgeable teachers, of exposure to the arts, of childhood friendships… of normalcy. The loss sits with them as they try to write English words, often quite foreign from their home-language alphabets. It sits with them as they learn to meander through an 1800-student school, navigating between seven classes with a schedule clutched in their hands and a few English phrases on their lips. The loss rests behind their smiles, below their tears, inside the quietude that comes with the overwhelming dilemma it means to be a Newcomer.

They are boys and girls, young men and women. Some have left their entire families at home, their desperate search for freedom forcing them to live with distant relatives or foster parents. Relatives they may have never met, who often already have a house full of people, where they have to sleep on the floor and pile on top of four cousins and fight for a bit of food. Foster parents from different cultures than their own, different belief systems, different foods, and different languages.

Newcomers are delightful. They beg for extra work and practice new words every day. They love their teachers because, unlike back home, none of them beat them here. They love their teachers because they know their teachers have the knowledge and the key to living here. They love their classmates and support each other by listening to the others’ immigration stories, helping each other translate, and making new friends from all over the world.

Newcomers have seen things you would never want to see. They have scars from blasted glass or fires or untreated childhood diseases. Some have lost babies; some have lost mothers, fathers, friends. Some have seen the eye of a war between a government and its people or between the gangs that rule the streets. Some of them come from such beautiful places that you can feel the blue sky, the mountains rising up, taste the crisp air, engorge your ears with the sounds of people laughing and praying. But those places were taken from them, often so suddenly their families didn’t have a chance to say goodbye to all that beauty.

They are dedicated. They commit their lives to improving their lives. They have seen the worst and would never want to go back to that dark place. Yet they yearn to go back to that dark place, their childhood, their homelands, their people, only to improve it, to save the ones left behind. They will take two buses or three trains to trek to our school, to indulge in working with adult interpreters from their own countries, to partake in our glorious Giving Grocery, to survive and thrive with heavily-supported English education.

Who are Newcomers? They are the human beings you wish you could be, the royalty of second chances, the hope we have for the future of our world.

They are our students. And more than anything, they are our teachers.

Small Moments Make a Day

a touch of snowfall

brings beauty to commuting

and calms my heartache

my name in Dari

made for me by my student

language: such a gift

Special Delivery

For You, For Me

hospitality:

the heart of an Afghan home

(how sweet the tea tastes)

Road Trip 2022, Day Ten: Gaps

through Cumberland Gap

we drive down to Tennessee

and stand in three states

it’s been many years

(the gap between visits here)

and everything’s changed

Pappy’s room is new

with the antique furniture

from their grandparents

a whole new kitchen

to fill Donna’s empty nest

with the light of love

this generation

will take the time to teach them

and fill in the gaps

they’ll learn who came first,

what they fought for, what they lost;

close gaps, open eyes

Breathing Through

June: a harried month

with all the joys and sorrows

that make up this life

Tomorrow Morning

My husband finishes work at 16:00, but he invited me to dinner in the cool uptown neighborhood where he works tonight. Because he had to “flip a switch”, as the four of us girls teased him, at exactly 18:00, and he couldn’t be late.

And we won these smiles.

Someone with a camera (my camera) took our photo. A nice white woman with a GoldenDoodle sitting next to us. On a Tuesday in May that should have been eighty degrees but it was only fifty and threatening rain.

Threatening.

But it wasn’t a real threat. It wasn’t an 18-year-old one of my students who walked into an elementary school in Texas to kill three teachers and EIGHTEEN 2nd-4th graders.

Nope. That life, that teacher life, is for tomorrow morning.

Tomorrow morning, I will rise at dawn, or just when the bluejays call me awake. I will walk my dog two miles through my Denver neighborhood. I will kiss my blue-collar husband goodbye and let my baby daughter drive me to the high school where we live/work. And we will walk into the Italian-brick-National-Historic-Monument of a high school and pretend that we don’t know the kid who could walk into an American gun store and kill the next generation in ninety minutes.

And I have worked for twenty years in this profession where my heart breaks every GODDAMN DAY in an attempt to keep that kid from doing that.

And you know what?

Tomorrow morning, I am going to see my recently-arrived refugee students who spent thirteen years on a list or thirteen harrowing months waiting in line or thirteen lifetimes waiting to come to the savior that is America, and try to explain to them, in my broken Dari/Spanish/Arabic/Pashto… that we are just as broken as them.

Tomorrow morning, I will rise at dawn after a night without sleep, and I will be there for them, trying to convince the boys that the gun store doesn’t exist and the girls that they have a future that includes educational advancement, no forced marriages, and a life that they can create.

And look at my girls.

Just take a look at the three girls I have raised who have to face this.

Tomorrow morning.

And Biden, you’re going to give a speech? And Governor Abbott, and Donald FUCKING Trump, you’re speaking at the NRA convention this Friday, I hear?

And what the FUCK are you going to say? Thoughts and prayers?

Are you going to be there tomorrow morning, when the blood of eighteen elementary students is still staining our hands? Are you going to walk into that high school tomorrow morning, having that conversation with the kid whose negativity has walked him into the free-for-all, no-accountability gun store that is our nation? Are you going to sit by my side tomorrow morning as I try to make it through another day in a profession that vilifies and disgraces me with false promises and broken souls? Are you going to tell my Newcomers tomorrow morning that this really is the American FUCKING Dream?

No. You are not.

Tomorrow morning, before the alarm goes off, I will be awake. I will take my broken salary, my broken heart, and I will hug my kids. The only gun I will carry, the only bullets out of my mouth, are these words:

I am here.

I am here now. I am here later. I am here tonight.

I am here for you. For a million years.

And I will still be here for you.

Tomorrow morning.

Stairway F

H was in a mood today because she wasn’t feeling well, and we all suffered. She called out her former friend and said she wouldn’t participate in the therapy session (though she did) during the first class, and in the second class, she sat in the corner and wrote in her journal and did her work without a word.

When it was time to visit the school food bank before trekking home on the train, she was definitely not up to it. I looked at my recently-arrived Afghan girl whom H has been escorting to and from school every day, and H looked right back at me. They were both standing in Stairway F, not Stairway R, the one that leads to the food bank.

“Well… are you going to wait for R to go to the food bank?” (H’s sister and brother had already fled the premises and were five blocks down Louisiana Avenue, halfway home).

“We’re going home. She can’t go home alone.” It might have been a dirty look H gave me, an exhausted look, a middle-child look.

H is from Sudan and doesn’t speak R’s language. But she lives five blocks away from her, and even though the train takes an hour to bring them both to my school, I convinced R’s caseworker that it was worth her staying, that we have a food bank and a newcomer program with three hours of English and two hours of math and a summer program and therapists and patience, and this Sudanese family that lives five blocks away who could show her how to take the train… But what they wanted was an escort, a female escort, who would make sure that she would be safe.

(When we were learning past tense verbs yesterday via a story about a man who had a bad day, my para talked H through her horrible story about her bad day, where, just like the man in the story who missed his bus, she missed her train because R was late. And H is never, never late. And she nailed those past tense verbs, her long braids that her sister entwined spilling down her back like a river of emotion.)

I had to let them walk down Stairway F. (It was just a few years back that I discovered how many stairways are in our building. They go all the way up to X, if you were wondering how a school built a hundred years ago with three additions tries to fit the world into its walls. Stairway X is in the 1987 addition with the new gym and its fancy foyer and its secret passage up to the third-floor batting cage.)

I digress.

I let them go, and I walked the rest of my class down the second-floor hallway to Stairway R, to the food bank where my most-recently-arrived Afghan boy told me the whole story, through his broken English and broken heart and the translator app on his phone, about the series of scarred slashes on his arm.

“The Taliban?”

Scars so deep that they are still pink, as if cut by a suicidal knife, as if done yesterday. He has photos on his phone from the day of the event, less than a year back, when he was working in a pharmacy that the Taliban decided to bomb, shattering the glass on all the windows, sending the glass into his forerarm, his shoulder, his soul.

“Can you walk with me through the food bank and show me how to get the food?”

The patient Wash-Park mother was making a list of new students. He didn’t know just how to add his name, but his verbal skills are over-the-top amazing.

“How many people are in your house?” I asked because the form asks.

“Twelve. In two rooms,” he informed me, holding up two fingers to prove to me he understood.

“How many children? Adults?”

“Eight children and four adults.”

And before we had walked through, before we had picked out chai tea and lentils and halal meat and handfuls of fresh vegetables, filling not one or two, but three bags for him to carry across the city on two city buses, H appeared in front of me, cutting the line with R, exhausted and sick and putting her arm around her, making sure that she had as many bags of food that she could carry home to her huge family, and…

That is what it is like to teach Newcomer English. Find your H, take the right stairway, and fill your bags with food and hope.