I have a data tracking problem. It starts with the word itself which is used to put a number, instead of a face, on my students. Data. A Star Trek android. A mathematician’s daily routine. A financier’s dream.

Here is my data problem. It starts with the word itself. From Latin dare, “to give” to Latin datum, “something given.”

We ask them to give us everything. Their trauma (trainings throughout the year on the various levels of trauma which range from a singular event to chronic abuse to historical-impossible-to-erase-racial bias), their educational history, or lack thereof, their familial and cultural belief systems, their languages, their motivation (impacted by anything that ranges from zero to a thousand), their futuristic ambitions.

We ask them for everything. We ask them for themselves.

And they bring themselves, each little datum, into my room each day. They bring themselves to my meetings with colleagues when, upon realization during our DDI analyses, my co-teacher informs me that the majority of an entire section of her course can’t even read the sentence, “The cat sat upon the mat and spat,” let alone correctly analyze an SAT passage for grammatical inconsistencies.

“And how am I supposed to teach them how to read?” she ponders, a high school teacher for twenty-five years.

And how am I supposed to categorize my students’ data by skin color, as my school asks me to, to close the gap between my three-years-here Iraqi refugee whose favorite English words are cusses, who has adeptly adapted to U.S. culture so fluently that he can identify how absurd it is when people come up to him on the street, assume he’s Latino, and start rambling in Spanish, with the Rohingya Muslim who just entered my room from a refugee camp where the militia taught him a great deal of verbal English, but who has never spent a day in school, saw his parents murdered by this same militia, and can’t even read or write in Burmese, let alone English?

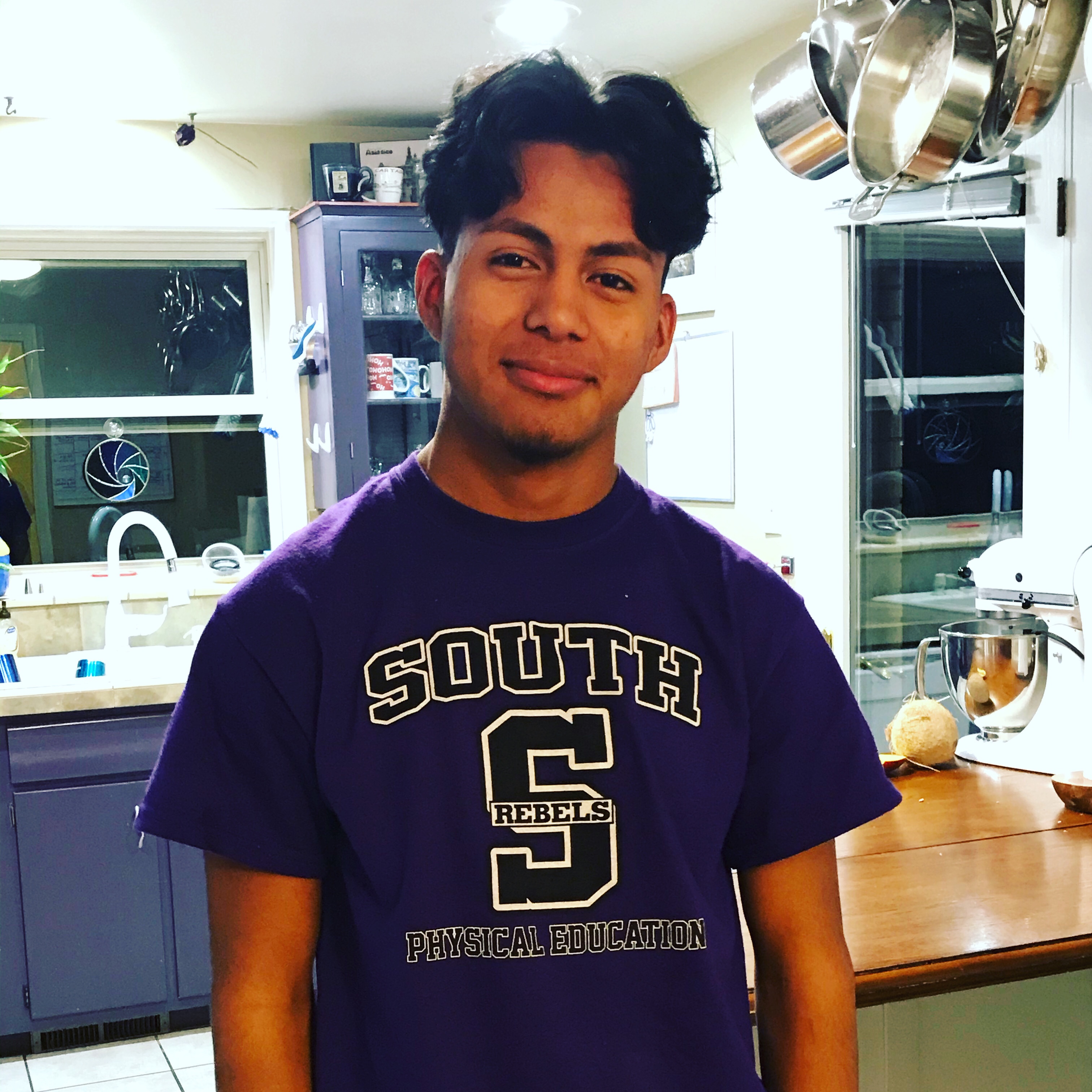

Or should I include the datum of A who spent five months trying to cross the border and another five months in three American detention centers with limited food, clothing, blankets, toothbrushes, or hope, only to be “adopted” by a white American suburban family, more or less ex-communicating his entire Honduran upbringing and culture because “it must be better here”?

Should I include each individual datum of the paraprofessionals who translate information for these students? Who have mostly arrived here as refugees themselves, but lost everything in war-torn, conflict-bound transport, including degrees in education, civil engineering, law, and decency, to get paid $15 an hour to translate to my kids the silly little things their crazy teacher says?

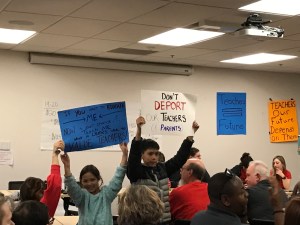

Should my, could my, data include my school district, that spends millions of dollars a year purchasing curricula that neither reflects my students’ faces or experiences nor is adequate enough to meet the various cultural and linguistic needs of every kid who walks into my classroom anxious to learn? My school district that employs and perpetuates incompetent leaders who have never taught an ELD course in their lives, let alone learned a second language, but choose inadequate resources for my students because THEY LINED THEIR POCKETS WITH GREED?

Should my data include what my Newcomers scored on their practice PSAT 9 test? Do you think that after two months of learning how to pronounce “th” and practicing “There is/there are” verbal phrases, they can accurately and beautifully read 500-word passages and correctly choose the best College-Board-meant-to-cherry-pick-college-bound-geniuses analyses?

Should my data include my professional development leadership meetings, where they show me every week, rather than asking me how it’s going, rather than ever once visiting my data meeting and giving me feedback, rather than taking a moment to understand what it’s like to be an English Language Learner, how to run a data meeting?

One that includes disgruntled teachers. One that includes major gaps. One that includes colonial white language and not the language of my students, and WHAT ARE YOU GOING TO DO TO FIX THAT, ESPECIALLY WITH THIS WHITE COLONIAL LANGUAGE WE THROW AT YOU WITH OUR “CURRICULUM”?

No.

My data is I. B. A. J. E. A. H. All their names. All their stories. All the letters of the alphabet (some of them just learned this alphabet from me, thank you very much).

My data is me talking to those two boys about how their counselor should have told them they didn’t have to take physics with the hardest teacher in the school, that they could have taken zoology and had a passing grade and the science credits they needed to graduate.

My data is every one of the dishes my Newcomers brought to the table after learning how to give directions, walking through the neighborhood and telling each other to turn left, stop at the light, learning how to bake brownies from scratch, learning that English verbs are actually quite simple, and they can explain to the entire class and the entire world how easy it is to make chapati, pupusas, patacones, flan.

My school, my school district, my world: they ask me for something given.

But what have they given to them?

Have they given them a better life? Have they given them words as powerful as redwoods, indestructible after a thousand years? Have they given them the hope they crossed the ocean, the river, the bitterness, to attain?

Have they given them the data that they will need to make their dreams a reality?

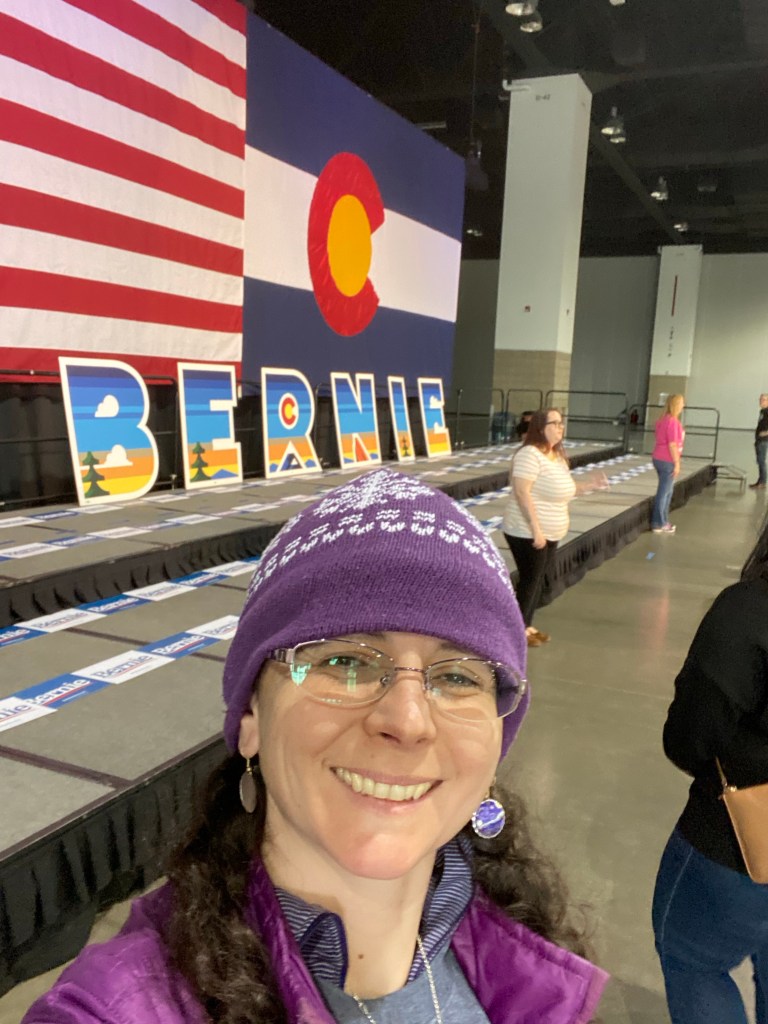

I have a data problem. It starts with the word itself. And it stops when I see their beautiful faces.

It stops here. Because they are all that matters. Not numbers. Not something given.

Something to give. Me to them. More than anything: them to me.