sometimes darkness wins

in the midst of a school day

until we find light

replaceable glass

that shatters understanding

as we question all

sometimes darkness wins

in the midst of a school day

until we find light

replaceable glass

that shatters understanding

as we question all

“Did you see that three blocks down, they’ve torn down a house and are building a mansion just like this one?” I complain on the drive up Florida Ave., noticing another mansion in place of a 1940s war home. “It’s happening. Right in our neighborhood.” Our neighborhood of 1960s NON-war, perfectly-good homes.

“Mama, all you do is complain. Do you realize that? You complain about everything.”

I think for a moment. We’ve been in the car for five minutes, and this is my first complaint. Give me SOME credit.

***Three hours later.***

My youngest has her exhibition night. She presents a video with her BFF about the endlessly inevitable impacts of Westward Expansion on Native peoples. She has drawn a calming coloring page with polygons for her math class. She has developed a filter to determine how best to eliminate toxins from drinking water.

And now she is participating in a Socratic seminar, sitting in a circle with her classmates, discussing “technology,” the parents hovering on the outskirts.

In the blink of an eye, the topic moves from the dangers of texting while driving to the dangers of guns. A very well-spoken and adamant eighth grader sitting two seats down retorts, “Guns don’t kill people. People kill people. My father is in the military, and soldiers have learned how to handle guns respectfully. With control.”

It is 19:22 on a Thursday night. I have sat through two 90-minute classes and two meetings and one long-short drive, fixed a put-together-leftover-dinner, walked the dog, walked to this “perfect” school, and begged my husband to join me for this one last event, only to realize the intense permeation of these ideas.

***Three hours earlier***

“Do you see it, girls? Right there. The original house is gone. Only the scaffolding for a mansion in its place.”

“And what’s wrong with that?” my oldest, money-hungry oldest, demands.

“The best part of living in this neighborhood is how real the people are. How middle class they are. NOT rich. Not taking everything out from under the rest of us.”

But all the people taking everything out from under the rest of us actually surround us. They are in my youngest’s classroom. They are five miles away, intentionally driving an RV into a hijabi woman, mother and aunt to the most precious students one could ever imagine the joy of having in a classroom. They are this thirteen-year-old’s mother, who intervenes in the Socratic seminar when some students suggest that in other countries, there are no school shootings. That in America, maybe we should focus on mental health rather than providing guns to all citizens.

A bulldog, she shadows her daughter, raises her voice, raises her hefty body in a darkened stance, and indirectly threatens the eighth graders. “We as human beings… We are ALL human beings, right? You as a human being have the responsibility to get help if you have mental issues. You have the responsibility. No one else. Guns don’t kill people. People kill people.”

I have to turn away. Suck in my breath. Stare at the wall. Clench my fists. Her teacher visibly notices my discomfort, walking towards me but not saying a word.

When I arrive home, all the news of the day is a heavy weight. My two girls who graduated nineteen months ago, who walked across Eritrea for fear of persecution, leaving their parents and home behind in search of a better life, who came to our country because their aunt lived here, who couldn’t tell me till the end of the year that the words of The Good Braider were so true for them, the protagonist counting her minutes on her cell phone, working extra hours to buy more minutes, were so true to them because they had to do the same to call home to their mother… And now?

And now some bastard who saw a hijabi Black woman walking home in the middle of a Wednesday from an ENGLISH CLASS rushed across two lanes to murder her?

But guns don’t kill people. People kill people, right?

“You’re not friends with that girl, are you?” I ask my baby daughter.

“God, no, Mama, she’s just awful.”

“OK, I’m just making sure because …” And I begin my rant about guns, the same rant they’ve heard their whole lives, the same rant that causes my middle child to hold up her hand and shout, “Enough with your opinions, Mama, it doesn’t really matter,” and then I hold up my ever-evil, ever-heartbreaking social media page where my close high school friend has to report that her Muslim son was threatened by a classmate to be shot that very afternoon, and I shout back, “It ABSOLUTELY matters, and this is why.”

It’s true. I complain about everything. I complain about injustice, and I will complain about it every minute of every day until the day I die. Injustice in the distribution of wealth. In immigration atrocities. In gun violence. In violent death from the gun of a soldier in the Middle East to the tires surrounding me in ever-so-fucking-golden-Denver.

I wish I could buy more minutes, too, just like Viola in The Good Braider. Just like Jumea and Salihah, who crossed mountains and oceans and discrimination to be given a chance that has been taken from them.

I wish I could buy more minutes of their smiles. Of how hard every immigrant I know works to build those mansions. To make this American Dream a reality. To put this darkness into perspective.

These are my minutes for today. My notes. They may sound like complaints, but they are tinged with the hope that someone will listen. Someone will donate. And someone will see that people don’t have to kill people.

At 12:39 a.m., my husband’s phone rang. A text message beeped. He rolled over and turned it off, not revealing to me the message, though I tossed and turned for the next fewer-than-five hours of “sleep” until my alarm startled me into a flood of my own messages. Realities of life in America in 2019.

One person, an 18-year-old child, lost and confused, dead before the day was over, shut down every major school district in a massive metropolitan area today.

This child, infatuated with the Columbine massacre that has been the backbone of her school upbringing, made “a credible threat” to “a school” and kept all the parents, teachers, officials, and students in a state of shock for the remainder of the day.

A girl, a lost girl brought up by school lockdowns, a mass shooting every day of her young life (of all of our lives), school shootings that have taken the lives of teens and six-year-olds, schools surrounded by armed police officers and security guards, and social media filled with conspiracy theorists and bullying…

Was she a credible threat, or was it us?

Is it us?

When will guns ever be considered a credible threat? When will gun stores who sell shotguns to 18-year-old out-of-state children be considered a credible threat? When will assault rifles be considered a credible threat? When will her online banterings (cries for help), the banterings of every filled-with-angst teen, be considered a credible threat?

One “shoe bomber” entered a plane. We remove our shoes in security.

Thousands of children died in car accidents. We put them in car seats.

Thirty babies died in baby swings. We recall the swing.

Are these credible threats?

Just as Sol Pais grew up with the Columbine tragedy as a backstory to her school experience, I have grown into my teaching career, my parenting life, with its everyday reality. I was a junior in college when the front pages of both newspapers in Denver were filled for weeks with the news of, Why? Who? How? All the major networks sent reporters that day for an emergency special. All of America, seeing the horrific scene played out on television, sat in numb disbelief.

Twenty years later, hundreds of school shootings later, there might be a few headlines for a day or two. A growing number of protests. A teary-eyed president’s remarks. An ignorant president’s remarks.

Yet, we have done everything but what we need to do to prevent the credible threat of another mass shooting.

We have lockdowns and lockouts at least four times per school year just for practice. Our kids huddle like rats in cages under desks in a dark corner of the classroom, always acutely unaware if this will or will not be the day they die.

We have more security guards and armed police officers walking the hallways. Some schools even arm teachers.

We watch videos to start the school year showing active shooter training for our district staff.

We have metal detectors, clear backpacks, and every exterior door locked to outsiders.

We have to talk to our kids, all of our kids–our students and our own–on a regular basis about reporting threats to Safe2Tell, about keeping an eye on suspicious students, adults, about what guns can and will do.

But…

The most credible threat in the world, the simplest solution, has never even been considered.

What if we just stopped selling guns? Assault weapons?

What if this 18-year-old child barely knew about Columbine because, after all the horrifying media attention after it occurred, our senators and representatives went back to Congress and represented the victims, rather than the NRA, and passed a bill that could save every credible threat like this from ever happening?

What if, at 12:39 a.m., I could dream a peaceful dream, and not have to think about what I’ll say to my daughters today and my students tomorrow?

There is only one credible threat here, and it is not an 18-year-old child.

It is ourselves. Our government. Our inability to bring the life, liberty, and security that we so proudly proclaim we offer in this “dreamland” of the United States.

i cry for the card, for his loss,

for his Iraqi-Syrian past,

for all the burning hours of summer school

where he committed himself

to finishing high school in three years.

i cry for his words, for his loss,

his inescapable self that has hidden

a kind face in a chaotic classroom,

his sly smile catching my every

snuck-in witty remark

(even when no one else could).

i cry for the system, for his loss,

shuffled by our government’s wars

between homelands that stole his home,

for his pride in Iraqi architecture

that he may never see again.

i cry for his future, for his loss,

for how unequivocally kind his soul remains

after all he has witnessed in twenty-one years,

for his brothers who wait under his watchful shadow,

for our country to give him a chance.

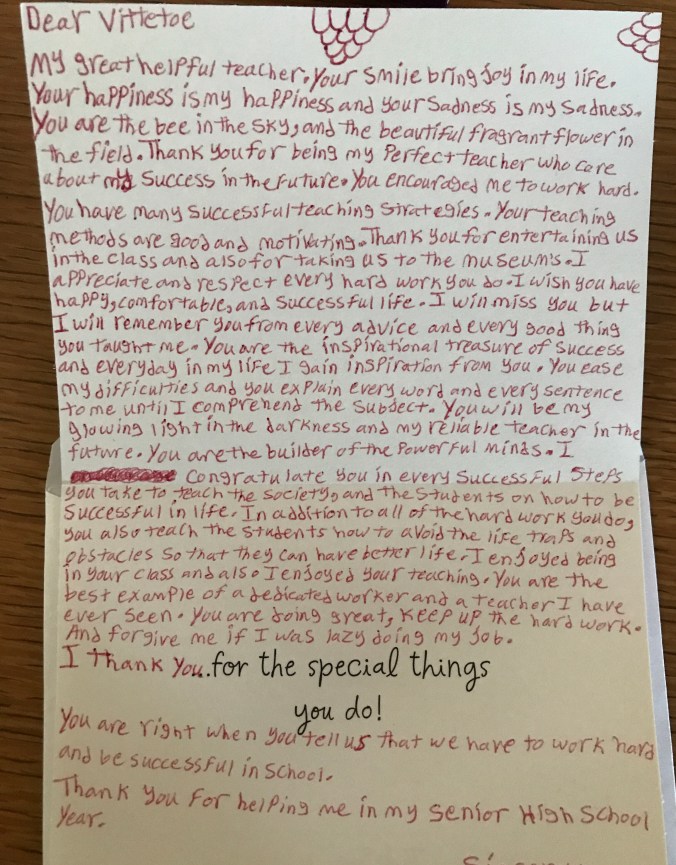

i cry for his words, for my loss,

to not have his presence in my classroom,

to have the nicest thing anyone’s

ever written to me

disappear with a graduation ceremony.

i cry for the world, for their loss,

for robbing refugees of their rights,

for keeping the beauty that is him,

that is within all of them,

from sharing their strength

with all of us, inshallah,

for a brighter tomorrow.

art intercepts life

on a cloudy Denver day

at the museum

social justice rules

when we create from our souls–

pen; paint on canvas

after a long walk

The Nightingale finally ends

(leaving with sorrow)

sorrow chases steps

across the gray of our lives,

of this cool spring day.

but i still find hope:

in neighborhood yard signs,

girls getting along,

in the purring cats,

the moist grass that begs to grow,

the chances that wait,

in my daughters’ eyes,

and the fight we all must fight

till tomorrow comes.

Wednesdays have turned into a ritual for Riona and I, as the older two get a ride home from the carpool and she has joined in with her expertise at helping me go grocery shopping (if expertise means begging me for Cheez-its, Naked juice, and blueberries…).

On this Wednesday, five days into Trumpocracy, the weight of it all is heavier than ever before. The two stores, the lines of people at guest services while I wait to buy bus passes, the shuffling of semi-broken carts, the weaving in and out of crammed-too-full aisles filled with Valentine’s candy and magazines and gift cards and everything, it seems, except the food I need to feed my family.

The knowledge that I carry with me now, of stripped healthcare, border wall building, claims of voter fraud, Muslim refugee bans, women’s healthcare denials, mortgage fees reinstated… It makes even the mundane tasks of finding the right brand of almond milk, of selecting a new variety of potatoes, of giving in to the Cheez-it bid, seem heavy and dark and worrisome.

How long will this variety of foods be here? I begin to wonder. How long will this variety of people be here? My darker self asks, as I hear a series of languages and see every skin tone meander through this shared space, this shared ritual of finding food.

At the second store, after I’ve sent Riona off on her own to fulfill half the list while I buy the bus passes, we count our items in the small cart to see if we can shimmy into the “About 15 Items” line behind four other groups. We stand behind them like a crooked tail as carts shuffle past, and slowly move forward to the monotonous beep of the register. As we pile our goods atop the belt, I’m proud of her ability to stick to the list. “Good, you got just the almond milk I like,” I smile down at her, and she grins back, “Of course, Mama. I’m not Daddy.”

A tall blond woman rings us up in a slow, methodical fashion. Riona, who has just finished checking off the last item on the iPhone grocery list, proudly clicks the phone shut and begs to put my credit card into the chip reader. “How does it work, exactly?” she asks excitedly, wholly unaware that my usual no has slipped into a dull yes because my mind is on all my Muslim students from all those countries on his list who will likely never see their extended families again (and not on who’s putting my card in the chip reader).

“Awww,” the cashier coos, “I wish I could be a kid again… although, I had a terrible childhood.”

I look up at her, the pale blue eyes, the straight blond hair, and the hint of an accent. She knows she has my attention now, though of course a line of people still waits impatiently in this express lane, wanting to check out, to go home, to pop open a beer and drink this day away.

“Have you ever heard of the Bosnian genocide?” she asks, and my mind flashes back to my first year of teaching when I had a student whose letter of introduction to me was, when I asked about his childhood, “Only an American would ask about that. Because my childhood was shit. My childhood was war.”

“Yes… I have had students who were from Bosnia,” I reply to the cashier.

“Oh, where do you teach?” she asks excitedly.

“South High School.”

“My sister went there!”

I’m reminded again of how connected our humanity is. She hands me my receipt, I tell her what a great school it is, and I grab the hand of my ten-year-old, whose childhood still lights up by the sushi we always share (unbeknownst to her sisters) before we drive home. Whose childhood is road trips and living in Europe for a year and grandparents who are right down the road and two loving, living parents.

We make our way across the parking lot, and she rams the cart into the speed bump. The eggs tumble to the ground and she frantically looks up at me, ready for the annoyance that would normally be present on my lips.

But I am crying because I don’t care about the damn eggs. I care about the millions of refugees, just like that girl in the grocery store, who won’t be coming here. About the thousands who have come. And the thousands who have been left behind. About the impotence I feel, the numbness that creeps into the corners of my days, as I face this new regime.

“What is it, Mama?” she asks, taking my hand again. I tell her what the girl said about the Bosnian genocide. About the papers Trump is ready to sign. About my first-year-of-teaching student.

We open our crunchy California roll and I put all the wasabi on one piece. She smiles, holding up the bottle of water for me, wanting me to douse it out. “Not this time,” I say, “I want to feel all that fire in my mouth.”

I want to feel something. To feel like I can go to the grocery store without crying. To feel like we live in a place where everyone is welcome, everyone is loved, and everyone is free. Where everyone has the chance to have a happy childhood.

Halfway home, she asks, “Can I have the last piece?”

“Of course.”

She pops it into her mouth and squirms in her seat. “Don’t worry, Mama, I’ll throw the package away before the sisters find out.” She hops out of the car and dances across the lawn towards the outside trash can. “It’ll be OUR secret.”

As usual, she is as happy as a clam. She doesn’t carry the weight of the media, the weight of the presidential pen, the weight of a genocide, as she goes through her days.

She has the gift of a happy childhood. And for now, that is the only weight I want her carry.

“We’ll never tell,” I smile back, the spicy wasabi still sticking to my tastebuds. I can feel the fire in my mouth. And for this moment, at least, I am only thinking about how happy she is.

About how glad I am to have my girls, my home, my school that is a safe haven for all the refugees, for the grocery store filled with a microcosm of the world where a refugee now works, and all the food our family will need.

Because it is something. It is enough. Enough for today.

our country is wrapped

in a cold and hateful tomb

i beg afterlife