Most people who hear that I have three, not two, daughters, send me a sympathetic look, or trade empathic stories of their own three or four girls, or commiserate in some form or fashion.

“Three teenagers? All at once?” Their shock and worry for my well-being come hand in hand with the realization.

Rarely am I praised or labeled blessed for such a thing. Because three is too many. Three girls, or three of any one gender, is too many.

But an accusation is a whole other ballpark that I don’t quite know how to bat for.

“Can’t you understand the plight of my daughter, someone who doesn’t have two sisters who are her best friends, and how lonely she must feel? And you sit here with your sisters and have a house full of friends and treat her that way?”

She stands at my doorstep. I recognize her voice, but I find my feet paralyzed in the kitchen staring at the pizza dough my youngest has spent the better part of a day preparing. My youngest, who righteously defends herself against the bullied petulance of her sisters, but outside of our family, has likely never said an unkind word to anyone.

“Do you not like my daughter? Do you have the decency to admit it? And YOU, what did YOU say to her? What did you do to her?”

I listen to my girls stumble over words as I put the scene together in my mind. One neighbor came over and spent the morning rolling out cookie dough, boiling water, squeezing lemons, and stirring iced tea. She and my youngest set up the lemonade stand at the corner and made a catchy but annoying hip-hop rant to woo passing cars: “Lemon-ade and cookies too, get your lemon-ade, doo-doo!”

After more than an hour and many dollars later, the pitchers of iced tea and lemonade were nearly empty before the third child arrived. My middle girl and I were still in the midst of the nightmare job of pulling tiny bits of crabgrass out of five hundred square feet of pink rocks, and my oldest had just pulled up with a shake and chicken nuggets, her hair freshly cut, offering everyone a taste.

The third girl stood at the edge of the scene, and Riona offered for her to help clean up, giving her two cookies and five dollars once the lemonade was gone.

“I want to know who called my daughter anus? Was it you?” I can feel her eyes burning into Riona’s, whose tears are already burning down her cheeks.

“We were just messing around. We say that to each other all the time,” the first friend pipes in.

But she is not done ranting. She lays on the (must-be) Catholic guilt of her daughter coming home crying, of being excluded, of the disgrace of the name-calling, pinning it directly on this household and “the fact that we know nothing about you three girls even though we’ve spent so much time with ___, and nothing like this has happened before.”

The snake that is Jealousy has slithered heavily down the block, consuming all air from my lungs, from my children’s stuttered responses, and choked us all into shocked silence. How venomous it tears apart a young girl’s heart, how twisted offhand remarks become when in the presence of new friends.

I begin to find footing to approach the mother, but she has stormed off before I can peel myself from petrification in my pocket-door kitchen.

Did she not take a moment, in her Mama-Bear attack, to think that it might be possible, just maybe, that her girl was feeling left out and blew the comment out of proportion? Did she want to find a scapegoat for the tears? Did she want her to lose a friend?

Tears are the only characters in the room once she leaves. Everyone has her version.

“She thinks we’re friends with each other?” the sisters exchanged snarky glances.

“I just offered her some of my ice cream.”

“I was weeding.”

“I gave her five dollars and a cookie.”

“I called her anus like I do every day, and I am NOT playing soccer with her no more.”

And what is a mother to do?

I present my Jealousy Lecture, fresh from my pocket and a conversation with my oldest from just a few days ago. “Just think how you feel when your sister gets something that you don’t, and how hurt you are, thinking that we favor one of you over the other one.”

Everyone nods, recollects, brings fresh tears to her eyes as they draw upon recent memories of Air Pods or Apple Watches or a damn raincoat two sizes too small and three years past being angry about.

But they get it.

“Why don’t you two make a card…”

They take the card stock, the permanent markers, the classroom supplies I am always buying for my classroom, and blatantly apologize as only children can: “I’m sorry you felt discluded.” “I’m sorry I called you anus.” “You are our friend.”

Too afraid to walk the block alone, I accompany them to the house. They timidly ring the bell, and the mother answers, her husband hovering in the doorway.

Perhaps the mother says something. Calls her daughter. Perhaps there is a vague apology to me for storming in and accusing my girls of something that they didn’t say.

But no one hears anything but his voice. Threatening. Thick with hatred. Eyes on the friend. “Don’t you EVER say that crap to my daughter again, do you understand me?”

I can almost feel the fist in his voice. The toxic masculinity as he repeats the command as if he is speaking to an enemy in the ring, a wife who won’t listen, a waiter who brought him the wrong drink.

Tears immediately fill her face as she backs away, unable to even speak the words of her apology to the young girl whose parents believe everything she says and have no idea how to handle any of it.

Riona puts her arm around her for the long block home, consoling her, telling her it’s not her fault.

In the retelling of events, Izzy asks, “Is he like that angry customer who tried to get us all fired for asking him to check the freezer for the pint he wanted?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

“Is he like that guy who cut you off and flipped you off?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

“Is he like Trump?”

Yes. Exactly like that.

And… I don’t have to explain. They already know, though no men in their direct life are anything like these men, and no women in their life would accuse without taking the time to understand.

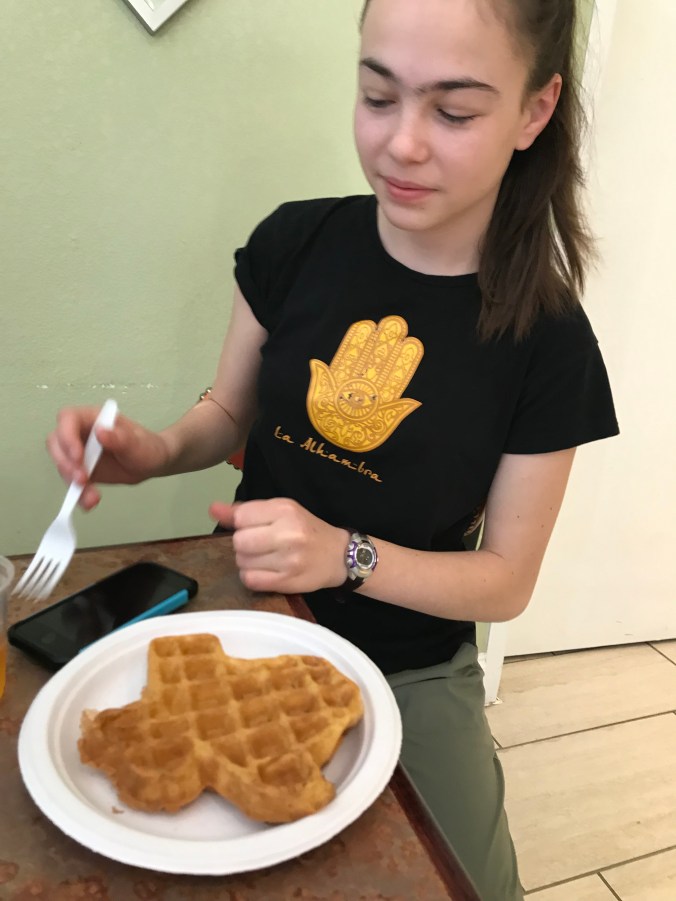

They enter, finish baking the pizza with the fresh-snipped basil and spinach from the garden, set up the hammock to eat it in, sit in the swing together, play Scattergories and act like best friends… if only for a couple of hours.

At least one of today’s accusations can have some validity.

At least I don’t need a sympathetic look for how I have raised them. How lucky I am to have a man who has never spoken a harsh word to anyone, let alone an 11-year-old girl.

And at least they know how to make lemonade out of lemons.