working mother

Winter Warmth

That Career Life

Timeless

Wabi-Sabi (Perfectly Imperfect)

Small Moments Make a Day

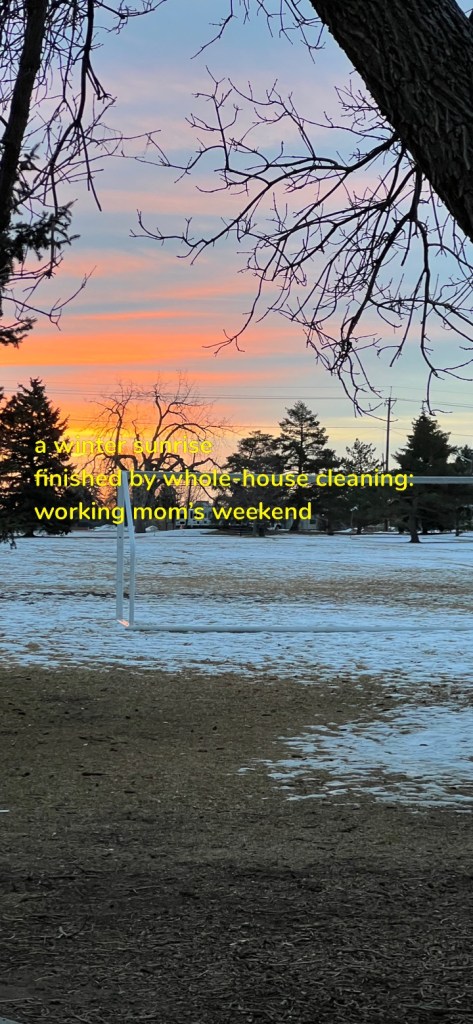

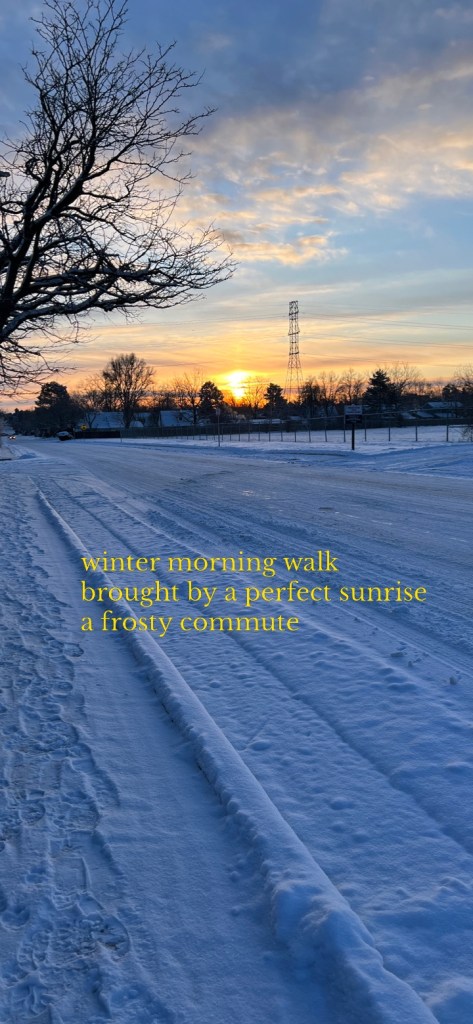

a touch of snowfall

brings beauty to commuting

and calms my heartache

my name in Dari

made for me by my student

language: such a gift

SkyView

Not Here.

If you had another job, you would be so annoyed by the coworker who couldn’t piece together fiber or the project manager who doesn’t know how to manage, and your day might be temporarily ruined. You would miss your lunch hour redoing someone’s work or you wouldn’t be able to tell your boss your exact opinion of his golf vacation in the midst of your short-staffing issue.

If you had another job, you would spend your lunch hour cutting fibers or sending emails or catching up on a spreadsheet, hoping for a break or a promotion or … anything else.

Anything but this.

If you had another job, you wouldn’t stop in your tracks in the middle of a lesson to let a severe-needs child work his way to his seat, an admin begging you to give him a pencil and a blank piece of paper because maybe if he could draw a basketball, he would stop rocking on his heels and shouting the word across the room for all the world, all your classroom of recent immigrants, to witness.

If you had another job, when the siren makes your phone and the PA system and the whole world bleep and vibrate, you wouldn’t be thinking about the announcement (seeking the nurse) at lunch. You wouldn’t be sending your middle daughter to investigate the health of your colleague whose life was already threatened more times than the number of weeks in this school year, only to hear this report: “There were people everywhere and a kid on the floor. The security guards were surrounding the whole scene. We couldn’t see anything.”

If you had another job, you’d see everything. The botched fibers. The boss’s vacation. The spreadsheet that tells you exactly what you’ve done right and exactly why you don’t belong here.

But you don’t have that job.

You have this one. And despite the pull of this dog lying on your calves with the persistence of a love so divine you couldn’t measure it, this morning or in any other moment, you are here now.

And you look at your refugees and think about the Afghan girl and the Afghan para, who both stood on that tarmac eleven months back in a country that will no longer allow them to attend school, let alone show their faces, and are up in the tech office trying to get a new computer while you stand here, trying to explain without Dari or Pashto words,

“It’s a lock… out. There is a problem outside of the school. Not here. Do you understand me?”

And all the while you are thinking about your colleague whose student yesterday held a girl at her throat and sprayed her with dry erase cleaner, now imagining that at lunch that kid was under the security guards’ hands, and that he escaped, and that he “is a suspect in the perimeter.”

And that your colleague could be gone. And that your daughter was braver than you, walking down there to report on truths that can’t be reported.

And that you have to teach a lesson about the BE verb and all its uses and “Yes/No” questions such as,

“Are you happy?”

Yes, I am.

No, I’m not.

And the boy who can’t read or write or take total control of his body won’t stop talking about basketball, and then soccer, and then eating, and his paraprofessionals finally come, and the Afghan para and the Afghan girl return unscathed, and when you look into her young and beautiful eyes and ask her to say, in Dari and Pashto, “Please tell the students that the danger isn’t here. It’s a danger outside of the school,” they all shout, “We understand you, MISS!”, and even after her translation, her reassuring interpretation of your words,

You’re. Still. Not. Sure.

And let’s make contractions out of these “Be” verb conjugations, my students! (He + is = He’s. You + are = You’re.)

If you had another job, you wouldn’t have to wait until the passing period to see the text from your threatened colleague.

“I’m OK. A kid passed out in my room during lunch. I don’t know about the lockout.”

You wouldn’t have to wait. You’d be sending emails, repairing fibers, or working your way through a mountain of paperwork.

You wouldn’t be standing in front of these kids who are trying to piece together the parts of a sentence and the parts of their lives that were left in another country.

You wouldn’t be you.

If you had another job.

Breathing Through

June: a harried month

with all the joys and sorrows

that make up this life

Stairway F

H was in a mood today because she wasn’t feeling well, and we all suffered. She called out her former friend and said she wouldn’t participate in the therapy session (though she did) during the first class, and in the second class, she sat in the corner and wrote in her journal and did her work without a word.

When it was time to visit the school food bank before trekking home on the train, she was definitely not up to it. I looked at my recently-arrived Afghan girl whom H has been escorting to and from school every day, and H looked right back at me. They were both standing in Stairway F, not Stairway R, the one that leads to the food bank.

“Well… are you going to wait for R to go to the food bank?” (H’s sister and brother had already fled the premises and were five blocks down Louisiana Avenue, halfway home).

“We’re going home. She can’t go home alone.” It might have been a dirty look H gave me, an exhausted look, a middle-child look.

H is from Sudan and doesn’t speak R’s language. But she lives five blocks away from her, and even though the train takes an hour to bring them both to my school, I convinced R’s caseworker that it was worth her staying, that we have a food bank and a newcomer program with three hours of English and two hours of math and a summer program and therapists and patience, and this Sudanese family that lives five blocks away who could show her how to take the train… But what they wanted was an escort, a female escort, who would make sure that she would be safe.

(When we were learning past tense verbs yesterday via a story about a man who had a bad day, my para talked H through her horrible story about her bad day, where, just like the man in the story who missed his bus, she missed her train because R was late. And H is never, never late. And she nailed those past tense verbs, her long braids that her sister entwined spilling down her back like a river of emotion.)

I had to let them walk down Stairway F. (It was just a few years back that I discovered how many stairways are in our building. They go all the way up to X, if you were wondering how a school built a hundred years ago with three additions tries to fit the world into its walls. Stairway X is in the 1987 addition with the new gym and its fancy foyer and its secret passage up to the third-floor batting cage.)

I digress.

I let them go, and I walked the rest of my class down the second-floor hallway to Stairway R, to the food bank where my most-recently-arrived Afghan boy told me the whole story, through his broken English and broken heart and the translator app on his phone, about the series of scarred slashes on his arm.

“The Taliban?”

Scars so deep that they are still pink, as if cut by a suicidal knife, as if done yesterday. He has photos on his phone from the day of the event, less than a year back, when he was working in a pharmacy that the Taliban decided to bomb, shattering the glass on all the windows, sending the glass into his forerarm, his shoulder, his soul.

“Can you walk with me through the food bank and show me how to get the food?”

The patient Wash-Park mother was making a list of new students. He didn’t know just how to add his name, but his verbal skills are over-the-top amazing.

“How many people are in your house?” I asked because the form asks.

“Twelve. In two rooms,” he informed me, holding up two fingers to prove to me he understood.

“How many children? Adults?”

“Eight children and four adults.”

And before we had walked through, before we had picked out chai tea and lentils and halal meat and handfuls of fresh vegetables, filling not one or two, but three bags for him to carry across the city on two city buses, H appeared in front of me, cutting the line with R, exhausted and sick and putting her arm around her, making sure that she had as many bags of food that she could carry home to her huge family, and…

That is what it is like to teach Newcomer English. Find your H, take the right stairway, and fill your bags with food and hope.