that blue sky beauty

that draws the world to us

through transportation

bleeds through their smiles

their too-cold impatiences

their want for fire

Denver can bring it

can bring them all to glory

to what we could be

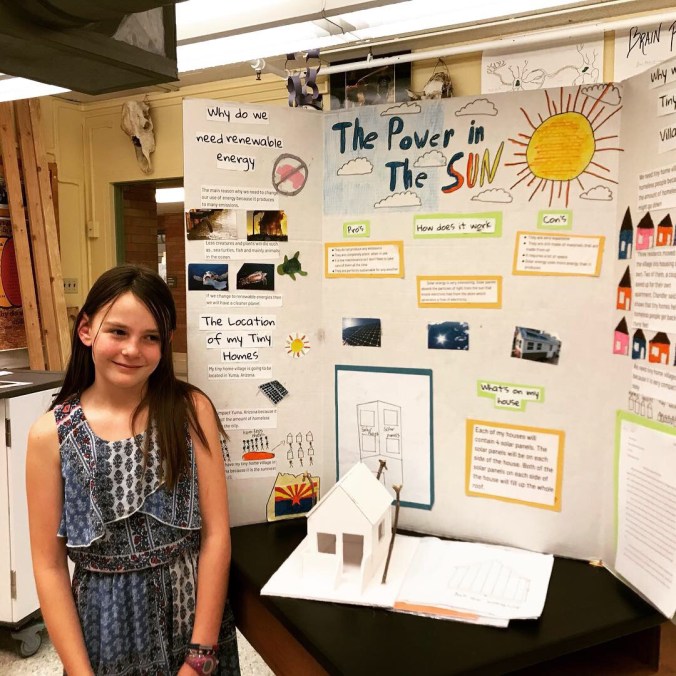

my teen girls cherish

our holiday traditions

cookies. candies. love.

never a year missed

as friends and family take turns

giving all colors.

my actor, artist

my sculptor, my filmmaker

my youngest daughter

to be burned badly

leaves irreversible scars

i know this too well

reminders can burn

with each of love’s harsh seasons

oft without reason

so much lost from this

this me, trying to be good,

trying to please you

for a true friendship?

i would do anything, love.

offer everything.

but all of love’s views

have left me with rejection

(unforgivable)

the season has passed

i am nothing but a post

burned and scarred for life

It’s not like when they were little. When getting the Christmas tree brought all the joy and excitement of the season. When they would clamor over each other, fighting for their chance to be the one to put the angel on the advent calendar on Christmas day. When nothing mattered more than preparing for the joys of the season.

Now, lethargically, with little effort and a few forced smiles, they give up on decorating the tree halfway through the ornaments.

“It looks good enough,” they whine. “Can we be done?”

I see that all the large paper and playdough ornaments still sit in the box, their imperfect candy-can cut-outs laying on top of the crumbling Christmas-tree dough.

“But what about these? Your preschool ornaments that you made?”

“They’re too big. They’re not as nice as the other ornaments. They don’t matter.”

“They don’t matter? But you made them for us when you were…”

But I can’t finish. Mythili cuts me off. “We’re not getting rid of them, Mama. Don’t freak out. We’re just keeping them in the box.”

We’re just keeping them in the box. We’re just pretending to smile. We’re just going through the motions of the “magic.”

I don’t even like this holiday. How could I? I wasn’t exactly raised a Christian. I’ve just gone through the motions myself all these years. The lights, the tree, the advent calendar (homemade), the decorating of cookies, the baking of zucchini bread, the holiday cards, the portraits with matching outfits, the pies, the hours waiting in line to waste money on Santa pics, the presents.

Trying to build traditions. Memories. A family.

But now, not even grown, not even gone, they are boxing up their childhoods, their simple joys, their everything I’ve tried to build for them.

No one will ever tell you how hard parenting is because it is impossible to describe. From the midnight collicky cries to the ambivalent teen and everything in between, it is a constant struggle to raise a well-balanced, sentimental, sweet, and loving set of small human beings.

Yet, we keep trying. We keep putting up trees and stringing lights and playing Christmas music and baking cookies and trying to take every ornament out of the box.

We keep hoping that they’ll remember this. These small moments, these annual events, these attempts to win their love.

We keep hoping that they won’t leave us in a box as they grow.

The day begins with tweaking. That is all that life is, really. Just one small tweak in a different direction and the result could be completely the opposite. If my daughter tweaks that steering wheel just a little more to the left, we could have a head-on collision. If I tweak my reaction to her left-leaning grip to a scream instead of a stifled breath, the whole day could be doomed by her admonishment of my “criticism.”

If you could just tweak your lesson by a few words, you could build up the academic vocabulary.

If you could just tweak your email a little bit, I would actually understand the task you are asking me to accomplish by the end of tomorrow.

If you could just tweak the fuck out of this pay scale, maybe I could afford to breathe.

The day ends with tweaking. Eighteen months into planning a trip with one of these multi-million-dollar scams to take some students to Costa Rica to complete sixteen hours of service, to have a purpose for their privilege, the rep from the company calls to inform me that no one else signed up for the service trip for that week, that we won’t be able to take that tour, that we will have to do the normal tour, pay a bit more, add an extra day, horseback ride, visit a national park, see the sea, be the fucking privileged bastards that we are, never making even the least bit of a positive mark on this cursed world.

“Are there any other options?” I ask after she has already said to me, “Was it your personal preference to do service or a school district requirement?”

I should have said school district requirement. I should have gathered up the words I have in my heart now, about how hard this has been to organize, how few students I’ve recruited, how my colleague can’t even come because we don’t have enough, how angry I am that after all this time, NOW, now I find out that I can’t even do the one thing I wanted to do? Teach English to small kids? Clean up a littered beach? Build a latrine? Something that makes a difference?

I should have tweaked my words, my never-present verbality incomparable to print, to thought, to hours later and all the tweaks I need to fuck this day.

During first period on a 90-minute-class block day, the few of us who had planning should have been feeling pumped. No students yet. No admin. No meetings. Just a moment to think about what we could do, what minds we could shape, what students would be there and what students we hoped wouldn’t.

And what did we discuss? A broken-down car, an Uber driver who saved the moment and makes more money than us in a day. Dog walking that pays double our salary. Being a trainer for Lowe’s. The emotional drain of being asked to please one hundred students, at least half of their parents, all of the admin, all of the district, all of the “failed” test scores, all of the data-driven nightmares, all in a day’s work.

It was a short discussion. We returned to our paperwork nightmare, our school district applications that freeze without warning on cheap PCs that break without warning, our plans that get interrupted by ten passes in a period, phone calls asking about missing students, requests for kids to attend assemblies, students who leave to pray, students who leave to get chips from the vending machines, students who won’t put their phones away, strings of emails five miles long trying to help the students who won’t help themselves, strings of want five miles long that stretch between breaks that, without, we’d utterly fail.

Could I tweak this? Could I just change five minutes of this lesson to ignore my Syrian refugee whose question (directly related to our reading, I promise) breaks me down to my core?

“Miss, why do white people think that they need guns? Who are they trying to kill?”

What academic vocabulary can I infuse into my white-supremacist rant, my explanation of three hundred years of slavery and colonization that we are just now taking the first steps to recover from, what words can I tweak to make her understand the weight of my response?

The weight of her question?

The weight of it all. The weight we carry with their questions, their presence… their absence.

My Honduran beauty, quiet as a field mouse, who ran away for ten days, scaring the shit out of all of us, her stepsister coming in teary-eyed and disheveled, whispering about the police, the older boyfriend, the fear. And when she miraculously reappeared after the break, I couldn’t do anything but wrap my arms around her, to tell her that everything was going to be OK, even though she knows I’m lying, that she has already flown across this border to live with a mostly-unknown father and stepmother, her mother back home working to her bones under the brutality of gang violence.

Could I tweak my interaction with this child, teach her how to take the SAT to the satisfaction of my school district?

Could I tweak this day, this or that news, this or that email, this or that career, to make all of it feel like it’s worth my time? My soul-bearing, heart-breaking time?

“If only I could write,” one of the teachers said this morning. “Maybe I could get some books published, make some money, get out of this.”

And she’s only five years in. Maybe she could find her words, find her magic, and escape the hell that we go through each day.

But then she wouldn’t have the stories. Those kids, they burn us and break us and… save us.

“This is my favorite class, Miss,” a boy with a 42% tells me after school, begging for work before the semester ends. “You are fun, and you make me work so hard.”

Not hard enough, I think. Could I have tweaked my thirty-person ELD class to differentiate for his specific needs?

I have a million messages from parents and students and admin and I shouldn’t be taking the time to write this post.

But no matter how much I try to tweak it, the work of a teacher never ends.

And no matter how much I try to tweak it, the love for teaching never ends.

And that is why I will rise tomorrow and face the same battles. The emails. The absences. The presence. The questions. The turns. The work.

With a little tweaking, maybe I can turn this work into a life. It’s only a matter of turning the wheel.

To avoid pouring water down the drain, I spend ninety minutes washing dishes in two pans, running water out to my new mulch to dump, and putting everything away while Bruce researches home equity loans and Trump tax cuts that hurt, rather than help, our current situation.

Behind the bars of my security door, I take this picture of the sewer company’s progress replacing a portion of our main drain.

Behind the bars of this security door, I hide from the American Dream. The one that we are all promised and few of us ever attain. The one where we could afford to buy a house, afford to deal with that house’s expenses, afford to send our children to college or even pay off the loans we might still have from our own degrees.

I hide from the dream of all of my grandparents, a combination of immigrants and endlessly American, one grandfather with an eighth grade education, one with a high school diploma, who were able to raise large families and pay off mortgages well before retirement. On ONE income.

I hide from the audacity of insurance that we carry on our homes, our health, our lives. From the premiums we pay that won’t cover pre-existing conditions (like pregnancy!) or pre-existing problems on our properties (like drains), or pre-existing hope–from all the thousands and thousands of dollars we pour into these plans that leave us empty, behind bars, unable to operate a backhoe.

I hide from the for-sale houses in my neighborhood that are now so outrageously priced that my family, and none of the other families on my block, would ever be able to afford to buy the homes we stand in.

Behind the bars of my security door, I am as insecure as everyone in my generation. The generation that faces housing costs that are equivalent to more than fifty percent of what we earn in a month. The generation of debt that is impossible to avoid even with the best budget. The generation that has made the choice to bring children into this world only to constantly think: why would I bring children into this world? Children I feel inadequate to provide for, children who will face even higher college costs, children who will be straddled with debt for their entire adult lives?

Behind the bars, I cannot see the buyers of the $769,000 remodel on the next block. Where they come from. What jobs they have. What magical formula they applied for that allowed them to take a mortgage that costs more than what our two incomes bring home in a month.

Behind the bars, I hear the Spanish language spilling from the mouths of the workers who have to dig a hole in a yard on a holiday. With perfect efficiency, they have repaired a ten-foot section of pipe within two hours, and they will move on to the next family’s crisis, and the next, and the next, before going home to houses on the other side of town that they also likely can barely afford, because we all know that the $6000 we just paid for that pipe is lining the pockets of a white, male, English-only CEO.

Behind the bars, I live in my dream house, my four-bedroom, two-bathroom, beautiful-garden dream house that we waited seventeen years to purchase. I raise a family of three daughters whose pay may never match their male counterparts but, despite this, whose intelligence and candor will allow them to live the life of their dreams. I share my meals, my home, and my love with my husband who has managed our finances to such perfection that we have flawless credit, making an application for an equity loan for both our properties (because nothing can just happen to this house–both need new main drains), virtually seamless. We both work hard at our dream jobs–teaching and telecom–in order to make this picture perfect.

With the door open, before they rebury the dirt, I snap a picture of our pretty kitty hiding behind my glass of stress wine.

I sit on our paid-for leather recliner and feel the cool breeze of early summer and think about my students who have crossed the world to be a part of this American Dream, and how hard they work to make that dream possible, to learn English and learn how to navigate the complexities of our society that sometimes make us feel like we’re all going down the drain. I think of how hard my husband and I have worked to make this day possible–to give my girls a summer trip to Spain, a year in Spain, to see nearly all fifty states–because of how careful we have been with our money. I think of the health insurance that paid for most of my husband’s surgery and how my grandmother’s baby sister died of a simple infection in her mouth after tripping up on a wooden popsicle stick, all because they couldn’t afford a doctor.

With the door open, we host family friends who make us laugh until we cry, whose daughter will join us in Spain, whose presence makes us appreciate what we have surrounding us in life–a life filled with laughter, love, support.

With the door open and the Spanish-speaking workers gone, the Siberian iris frames my kitty, my pet, my perfect yard. I know that I have given so much to get to this picture, and I know I still have more to give. I have daughters who are lucky enough to have access to all the technology, diversity, and coursework that comes from an urban education, and who will enter their adult lives with an open-minded understanding of the world. I have a house that we can afford and enjoy without feeling like our money is going down the drain. I have a job that brings the global perspective to every choice I make in one of the most beautiful buildings our city has to offer. I have a marriage that has lasted from childhood to adulthood, with all the post-adolescent turmoil and trauma, all the sorrow and joy, that comes with making it work for twenty years.

With my door open, I wait for the American Dream. Somehow, some day, some way, I will see how it is both easy and difficult to achieve. If I would learn to always open the door and move beyond the bars, I would see that not everything is going down the drain. I would see the beauty in every choice, the brutality in every loss, and find a way to make a set of silver linings sweeter than a sip of stress wine.

I would be the wife, the teacher, the mother of that perfect picture. That perfect picture would be me.

At the elevator, brace still on, crutch still under his arm, he tells me he thinks that a good return-to-work date would be June 4, five days before we leave for Spain. He seems optimistic as he hobbles down the tiled hallway, as we enter the carpeted office, as we check in and he holds the door open for a woman with a walker, pointing out, “It’s kind of strange they don’t have an automatic door in the orthopedic’s office,” to which she adamantly agrees.

On the plastic, paper-coated bed, he hands me the folder while the PA takes him for x-rays. After just a few minutes, the doctor enters with the films. He has photographs of the entire procedure. He intricately describes the meniscus (intact), the bones (drilled into), the ACL (torn and then repaired). Bruce and I lift our eyebrows at each other, barely able to distinguish the tiny details he points out in each picture.

In his cozy spinning chair, the doctor is also optimistic. “I think you can ditch the brace right now and ditch the crutches by Friday. Use the stationary bike on Sunday. By Monday, you should be walking around the block. Maybe driving.”

From the green paper folder, I begin to pull out the forms. First: short-term disability approval. A list of lines with dates, surgery and medication verification. Affably, he takes them in stride: “I’ll be sure to get these to the right people to fill them out.” Because he has people. Because he charged the insurance company $36,000, more than half of what I earn in a year, for an outpatient surgery that took less than 90 minutes. Because we live in the land of the free.

From the green paper folder, I continue to pull out forms. Bruce begins to tell him–without ever being able to finish because of the doctor’s rambling explanations, the doctor’s defense of his procedures, the doctor’s justification for not filling out anything–about wanting to return to work before Spain. I pull out The Form, the one that CenturyLink requires for him to be able to work: a release of liability for driving a company vehicle, an “if-something-happens-it’s-not-on-us, your-injury-better-not-affect-your-work” form.

From his throne, he glances at the wording. He throws in more anecdotes peppered with cussing colloquialisms. “In twenty-six years of doing this, I have never seen a company require a form like this. What if you’re a shitty driver? How can I, as your medical doctor, determine if you’re OK to drive? I won’t sign a form like that. If you get in an accident and hurt someone and I’ve signed this form, then it’s all on me.”

From my plastic chair, I listen to the tone of my twenty-years-spouse change from respectful to grainy. I can almost feel the lump at the back of his throat as he tries to go on. “Well, my supervisor is willing to let me come back on light duty…”

From his throne, the doctor interrupts: “What you’re going to be dealing with is HR, not your supervisor, and if HR says you can’t work, that’s where things get muddy when I start putting my name on these forms.”

From my plastic chair, I am counting down the hours in my mind until the moment I can let these tears actually fall. First I have to continue listening to this white-haired, privileged surgeon continue rambling on about lawsuits. Then, we have to make Bruce’s appointments for physical therapy. Next, we have to drive home and track Mythili’s progress on her bicycle, as I had no way to pick her up today. After that, I have to take her to her doctor’s appointment, where they will make commentary about how my thirteen-year-old hasn’t had her period yet.

From my plastic chair, I am frozen and without words. The doctor turns to me. “You look frustrated.”

Is that the word you would use? Do you think frustration sums up the past six weeks of my life?

“The thing is…” Bruce begins, “… I’m probably going to get laid off on July 30.”

The doctor has finished listening. “That’s why we have to be so careful when filling out these forms. This happens all the time, when companies decide you can’t work.”

“No, it’s unrelated…” he begins again, that painful lump sitting on top of his beautiful, sexy voice.

“Are you really not going to fill out the form?” is the only thing I can muster. The doctor hands it back to Bruce, asks if there’s anyone he can call, anyone he can talk to, any way he can go back to work without it.

From the tiny patient meeting room, he stands. He shuffles us out the door. He guides us to his people who will make the next appointment. I place The Form neatly back inside the green paper folder.

I think of a few cussing colloquialisms I could shout. I think of hindsight, all of it. Of next year’s ski passes we wasted $2300 on. Of the thousands we’ve already spent in this office. Of the four weeks at seventy-percent-pay he’ll get for short-term disability. Of the thousands we’ve spent on Spain that is gone and tarnished before boarding the plane.

But I have no words in these moments when I have bowed down to our litigate society, our corporations’ fear of liability, our doctors’ refusal to help the little man other than spurting cussing colloquialisms while trying to relate to us.

At the elevator, his brace in my hand, crutch still under his arm, I don’t speak. Picking up Mythili, exhausted from her bike ride, I don’t speak. At the following doctor’s appointment, where, as usual, we only get to see the PA, I cross my arms and don’t speak, forcing Mythili to respond to questions about who she lives with, how she likes her sisters, what kinds of food she eats.

From my recliner at home, I do have a few cussing colloquialisms for the orthopedic surgeon. I could spout them all day, all night, every waking moment of the past twenty years of marriage, every waking moment of my life as a not-quite-middle-class American who just needs A GODDAMN FORM SIGNED SO WE HAVE A FEW PENNIES TO OUR NAME…

From my recliner at home, the words are useless. All the words, all the work, all the life we have put into living, everything feels useless.

And there is no cussing colloquialism that will bring me that doctor’s signature, bring my husband his job, bring me some peace. So why bother spouting them at all?